There is an interesting story about Ajoy Chakrabarty, the genius and probably India’s finest classical singer. During the recording of show for Zee Telefilms, he exhorted his daughter, Kaushiki, to sing an old one, Saat Bhai Champa, even as he explained the notes to musicians on the stage. And then, after a pause, Chakrabarty looked into the camera and said it was high time people need to close the chasm that existed in India between Classical and Western music. Everyone should sing whatever they love, said Chakrabarty. “Many ask me why do you sing songs of Kishore Kumar, please do not do it. It hurts our feelings. I told them they should all stop this Panditji, Panditji business. Let people sing whatever they want, and if they can sing both classicals and Western songs well, applaud them and do not criticise.” Chakrabarty reminded me of the 1980 Telegu language movie, Sankarabharanam, where the protagonist JV Smayajulu said a similar thing to a gang of boisterous rappers, silencing them after he performed a song with perfection. And when it came to the turn of the youngsters to do a Classical one, they collapsed within seconds. This was no power show, Sankara helped the rappers understand the genesis of music and told them not to slice music into various compartments.

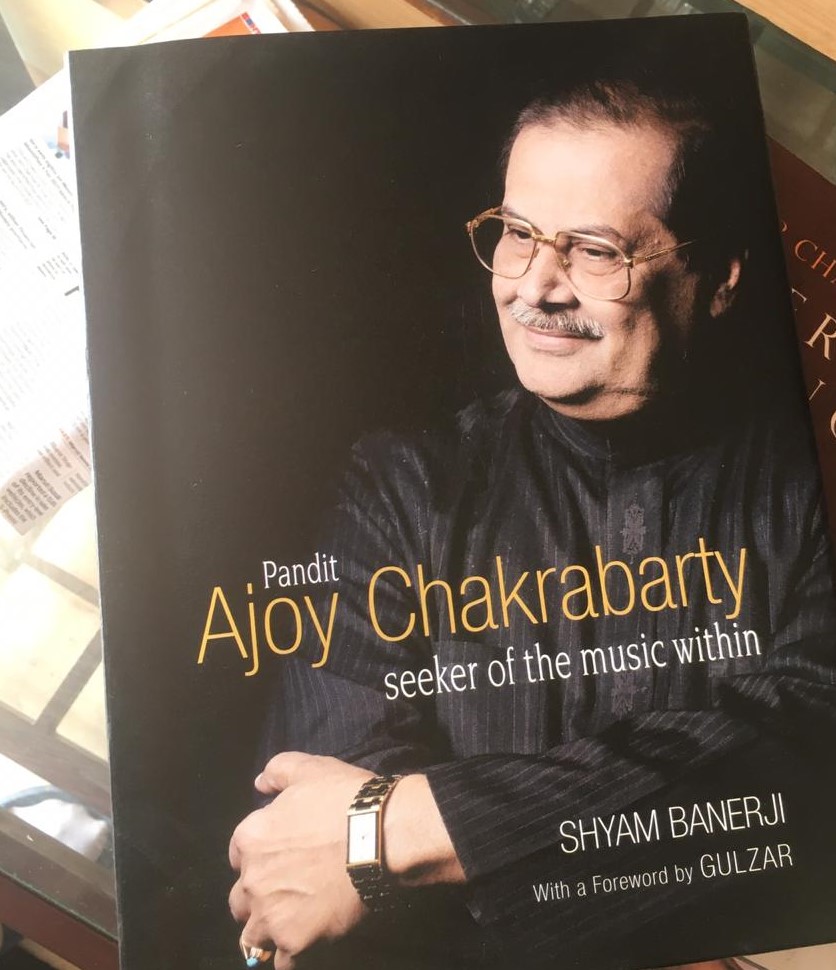

Chakrabarty is a root man, seeped into music, Shyam Banerji’s wonderfully scripted book, Pandit Ajoy Chakrabarty: Seeker of the music within – a product of Niyogi Books — explains the man and his music, and his life and struggles. I loved the chapter — all have a signage of the word Ga on top — where Banerji talks about Chakrabarty’s early days when his father, Ajit Chakrabarty, bought a dismantled weaving loom from Mymensingh (now in Bangladesh) and wanted to earn some extra cash by weaving Sujani, a quilt made from recycled sarees. Read these lovely lines: “The click-clack of the loom was a rhythm that I soon got used to. What I loved most was my father calling me and asking me to sit on his lap while he wove the cloth. Matching the beat of the loom, he made me practise the sargam.” Ajoy Chakrabarty looked at the colours and heard the sound of the loom for hours, it was absolutely enchanting for him.

The rickety loom was his gateway to life, Ajoy Chakrabarty remembered his music forever.

Many moons later, sarangi maestro Pandit Hanuman Prasadji Maharaj, told Chakrabarty that he (Hanuman Prasad) was happy at Chakrabarty’s usage of laya in his songs. Chakrabarty’s father was probably standing close. He instantly quipped: “Well, it pays to listen to a heavy dose of chautal, teevra and dhamaar at a very young age (he was referring to the kirtan sessions). Singing kirtans — Bengali Holy songs devoted to Lord Krishna — did not help Ajit Chakrabarty earn enough cash but grounded him in musical brilliance, his son Ajoy happily walked on the pavement of gold.

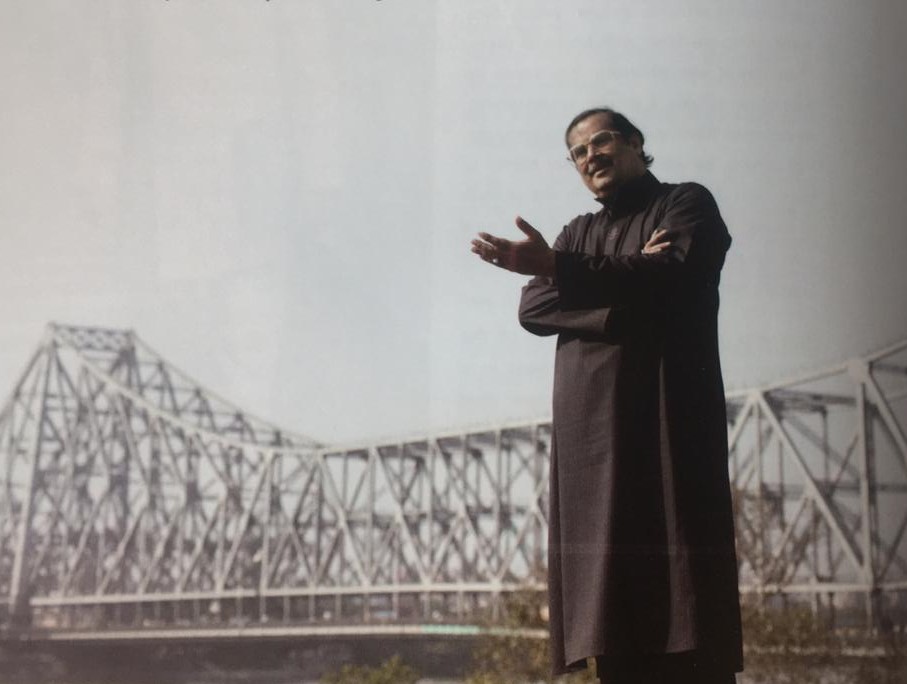

Biographies of legends can always be boring if its too, too laudatory without much insights, almost like the tomes written on cricketers and film stars. They rarely tell you the right stories, do not say why the batsman failed for three successive seasons and why as many as seven movies one after another did not work for an actor India knows as a superstar. But this one is different, it scores because it has both pain and gain. It has some of the most fascinating insights about the man who once stood close to the mighty Ganges in Kolkata like a character from the 1951 Jean Renoir film, The River, to shoot a commercial exhorting non resident Bengalis to return to Kolkata and boost the economy of the state. The Ganges, Ajoy Chakrabarty and his music was the highlight of the film. The book, time and again, explains why the protagonist has earned both name and fame, how hard, hard, hard he honed his skills to emerge as the Big Boss of Indian Classical Music. And how the Ganges remained an integral part of his life because he lived close to the river, almost like his gurus who could make out by the rustle of his slippers that Ajoy had come for his music lessons. I read how his father took an expensive loan from an Afghan trader — once Bengal had loads of them offering both dry fruits and cash — to buy a tanpoora for Ajoy. The instrument cost ₹90 in those days and Ajit Chakrabarty eventually ended up paying a whopping ₹300. Sounds lovely in these days of unpaid loans and non performing assets (NPAs) of the nationalised banks (isn’t it a whopping ₹8 lakh crores?). In those days, how many could have paid

₹220 extra for an instrument costing just ₹80. This was not just for music, this was also for life, this was also for the future of a rising star, Ajoy Chakraborty.

Ajoy Chakravarty wanted to do things in style. He wanted blessings from the Gods, was very, very keen to meet up Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Chakrabarty loved Khan’s music. Chakrabarty waited for an opportunity to meet the legend. But getting across to Khan was very, very difficult. Eventually, on a balmy morning in 1966, Chakrabarty met Khan in the corridors of the imposing All India Radio building in Kolkata. Chakrabarty touched Khan’s feet and the latter remarked instantly: “Jeetey raho beta.” Chakrabarty, then a teenager, was floored by the humility of the legend. Khan died on April 26, 1968, around the time when the UK pop charts buzzed with What a Beautiful World. Chakrabarty was crestfallen. He told the author: “I had come to regard Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Saheb as my ideal. I had heard so many tales of his generosity, his personality and his devotion to music. I wanted to be like him. His passing away was a heavy blow that weighed me down for days. There was a sense of gloom.”

Banerjee, the author, explains how Ajoy Chakrabarty was encouraged by his father to rise and sing again, not to be depressed because of the death of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. It seemed to me — the author does not write this one in the book — the rise of Chakrabarty was like that of the proverbial Arjuna from depression in the battle of Mahabharata, the words of Lord Krishna ringing in his ears, words that eventually formed the Holy Gita. For Chakrabarty there was no battle, no armies, no bows and no Godspeed fired arrows. Chakrabarty had to emerge from gloom. Eventually he rose, Chakrabarty recharged his batteries with that single memory of meeting his God in the corridors of AIR. He was back again, and there was no looking back.

Wonderfully written, the book is like a bangle studded with precious diamonds. I loved the one where the author explains how he — sitting in front of a radio — took notes from Tagore songs. The idea was to write down the lyrics and notations of each word of the songs and the transition of each note in a span of 15 minutes — obviously it was an AIR programme — and then emerge stronger. Chakrabarty remembered lines from his favourite Sukumar Ray poem, Ei Dekho Pencil, Notebook Ei Haathey (which translates into Look Here Is My Pencil, And Notebook In My Hand). And then, after training hard, Chakrabarty impressed his Guru Jnan Prakash Ghosh, who often asked his students to repeat what he taught. On that day when Chakrabarty outsmarted everyone, he had learnt by heart as many as 17 compositions. It was like scoring a hat trick in front of the coach, and also the club owner.

In a world of styles and brands, Chakrabarty does not need special hairdos, nor he needs a Merc or a designer kurta to make a statement, he rarely talks about his performances. He is an unusual musician who is at ease at the various musical conferences, and also at the lobby of a five star hotel jam-packed to receive Shah Rukh Khan. Once he used to sing like Munawar Ali Khan, only to be rebuffed by his father. And then he developed his own style. A style of singing the world loved, loved and continues to love. His inspiration comes from an extraordinary insight into the structure of ragas. He once told a reporter that he sees his place at the feet of Saraswati, the Indian goddess of learning who rides a swan and is worshipped at the start of the new year. I have a feeling Chakrabarty prides himself being Paramahansa, the swan who drinks milk by separating it from water. The title in Bengal, till date, is reserved for the sage Ramakrishna who was born Gadadhar Chattopadhyay.

What a lovely read, and imagine the book is unjustifiably priced at Rs 1500. If I was a publisher, I would have priced it three times the current price. Those interested in music make some right investments, and not seek all answers from Alexa or Google. They must buy the right kind of books to enrich knowledge. All music schools must pick up copies of this one and make it mandatory purchase for its students. Will they do it? If they do, the publisher will earn some decent cash.