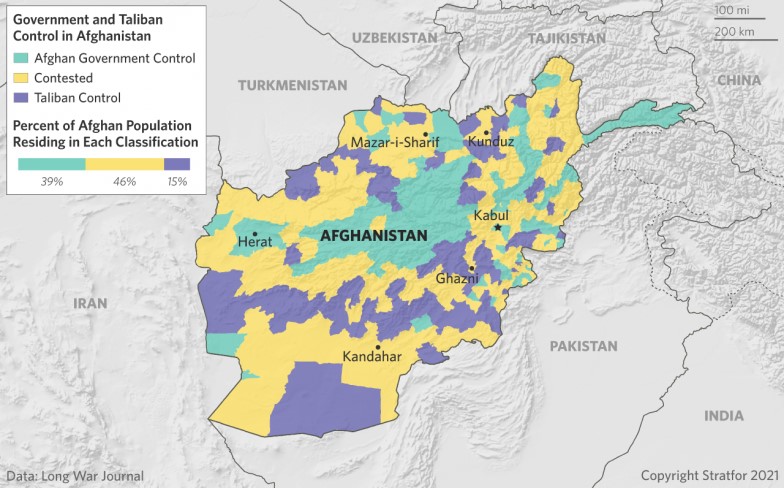

‘We have won the war, America has lost’[i], says Haji Hekmat, Taliban’s shadow Mayor in Balkh district to BBC correspondent on 15 April 2021. Interestingly the government forces stay within their base, as the territory belongs, or is controlled by the Taliban. This is the case in many districts/towns in Afghanistan. In addition to a stronghold in the strategically important Southern province of Helmand, the Taliban controls or contests territory in nearly every province, and continues to threaten multiple provincial capitals.

Taliban has control of the Southern and South-west portion of Afghanistan. On 3 May 2021, a series of bomb blasts outside a school in Kabul killed dozens of people, mostly students. The death toll in a horrific bombing at a girls’ school in the Afghan capital has soared to 50, and over 100 wounded, the Interior Ministry said on 4 May 2021. Officials blamed the Taliban who denied they were involved in the bombing and condemned it. Meanwhile, the hashtag “AfghansWantPermanentCeasefire” trended in Afghanistan on Facebook and Twitter in the lead-up to Eid[ii]. Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid told the Reuters news agency that the social media trend was an “emotional thing” and that the group “respected” these emotions. “But a ceasefire is something bigger than emotion, it is related to the larger issue of our country,” he said, adding that there would be no permanent ceasefire until the group’s goal of restoring an Islamic government is achieved.

A three-day ceasefire agreed by the warring Taliban and Afghan government come into force as celebrations of Eid-ul-Fitr got underway, after weeks of heavy fighting across the country. The temporary deal starting 13 May 2021 was proposed by the Taliban and agreed to by President Ashraf Ghani. The Taliban and the Afghan government launched peace talks in September last year, but progress has stalled despite international efforts to jump-start the negotiations. Ceasefires in the past have largely held in what is widely thought to be an exercise by the Taliban leadership to prove they have firm control over the myriad factions across the country that make up the hardline movement. While the Taliban have avoided engaging US troops, they have stepped up attacks against Afghan government forces.

Taliban Continue to Capture Territory in Afghanistan

The Taliban have reportedly captured at least twenty-six Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) outposts and bases, along with four district centres, in the provinces of Laghman, Baghlan, Wardak, and Ghazni since the beginning of May[iii]. On 15 May after the ceasefire announcement, Taliban fighters seized Nerkh district, which lies in Wardak province about 40 kms from Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul. Several highways run through Nerkh. While the US and NATO forces have pledged to withdraw their troops by September 11, the US military has completed an estimated 16–25 percent of the process of withdrawing from Afghanistan, US Central Command said[iv]. Military officials said they hope to have troops fully withdrawn by mid-July. The NATO led ‘Resolute Support Mission’ has indicated that its withdrawal will be co-terminus with US forces.

Afghan Government forces conducted operations last week of May 21, that aimed to retake four districts in central and eastern Afghanistan from the Taliban, according to reports. The defense ministry said at least ninety Taliban fighters were killed across eleven provinces in a twenty four hour period. The Afghan Taliban on 26 May 2021, warned nearby nations against allowing the United States to use their territory for operations in the country after they withdraw from Afghanistan. On 25 May 2021, Australian PM Scott Morrison announced closing its embassy. Taliban reacted saying it will provide ‘safe environment’.

The Taliban has conducted sputtering talks with the Afghan government in April 21 in Turkey. Taliban has also promised to renew attacks on US and NATO personnel if foreign troops are not out by the deadline; and said in a statement it would not participate in “any conference” about Afghanistan’s future until all “foreign forces” have departed. It is not clear whether the militants will follow through with the earlier threats given Biden’s plan for a phased withdrawal between now and September[v].

Trump’s Doha Peace Accord followed by the Biden Peace Plan

Trump astounded the world after more than a year of direct negotiations, by signing a peace agreement on February 29, 2020 (Doha Accord) with the Taliban, that set a timeline of 18 months for the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan. Taliban pledged to prevent territory under their control from being used by terrorist groups and enter into negotiations with the Afghan government by March 2020, which were tentatively started in September 2020 and immediately floundered.

The Biden administration has proposed a modified peace plan to the Afghan government and the Taliban, seeking to bring violence to a halt and form an interim government. The proposal included many elements; first, a UN-led conference of representatives of Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, India and the US “to discuss a unified approach to support peace in Afghanistan”; share written proposals with the Afghan leadership and the Taliban to accelerate talks. It urges both sides to reach a consensus on Afghanistan’s future constitutional and governing arrangements (the Taliban and the Afghan government still disagree on fundamental issues, including whether the country should remain a republic or even retain any features of electoral democracy); third, find a road map to a new “inclusive interim government”[vi]; and lastly, agree on the terms of a “permanent and comprehensive ceasefire”.

Essentially, the Biden administration is attempting to embed the peace process in a wider regional framework. The Biden administration has chosen a more decisive course in Afghanistan and has to make substantial movement on above aspects before final withdrawal. Cutting all rhetoric to the bone, ALL Nations want mainly two things, which need not necessarily be aligned to Afghan interests specially its people.

- An Afghanistan aligned to their interests.

- Their strategic space, influence and economic payoffs are bettered, whatever the political dispensation, while ensuring ‘no spread of jihadi culture leading to terrorism[vii]’.

Despite this new agreement, there is still no official ceasefire in place, and both sides including the US and NATO forces have launched attacks (US air targeting has actually increased) on each other till date. Taliban have restricted their attacks on ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces), their bases, government targets and made substantial territorial gains. The Taliban have also carried out high-profile attacks across the country, including in Kabul. There is also a disagreement on the timing of the release of five thousand Taliban prisoners. The Taliban expects the prisoners to be released before talks can proceed, while the Afghan government plans to release the prisoners after the negotiations make some headway.

The Islamic State in Khorasan– IS(K) has also continued to expand its presence in several eastern Afghan provinces (sources talk of five provinces), continues to carry out major attacks in Kabul, and is responsible for an increase in suicide attacks targeting civilians. Uncertainty surrounding the future of international donor assistance has strained the Afghan economy. While the United States, its allies and international institutions and NGOs have pledged to provide support to Kabul, the transition to a peacetime economy risks further destabilizing Afghan society by inflating the budget deficit and increasing unemployment rates.

Regional Geo-Politics: China and Pakistan Commons

Once Taliban comes to power it will use jihad and terrorism to create trouble, and exploit the façade of ambiguity. The longer the conflict more clout China and Pakistan will have with Taliban and thus in Afghanistan. They will enhance their geo-strategic and political clout in the region and leverage it with Iran, CAR (Central Asian Republics), and Russia. They will try to keep India out of Afghanistan, and constrict its strategic space.

China:Integrate CPEC with Afghanistan (Pakistan may not be too pleased), enhance land route of BRI towards CAR, Russia and Europe.

Pakistan: Cement its notion of strategic depth against India, keep Durand Line issue quiet and formalise it, opportunities for trade, entry into CAR, access to Middle East, influence Iran and play power broker in Middle East specially KSA (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) and Turkey.

Russia: Russia’s own security and geopolitical interests make it an interested party in a stable Afghanistan and in putting an end to armed conflict in the region. Its concern is that in the event of heightening instability, threat of extremist and radical ideology and violence could spill over into Central Asia and cause destabilisation close to Russia’s borders.

Iran: Seat of Shia Islam, Iran has historically been at ideological odds with a powerful Sunni Taliban. Tehran nurtures high-level contacts with the Taliban aimed at stopping the growth of the Islamic State (Khorasan) in the region and get US out of its underbelly. Currently adopted two-pronged approach; one regional in nature, and second in the context of Iran’s fractured relations with the US.

The Flipside. There is also a flipside to Taliban usurping power or having a major say in geo-politics in Afghanistan. It can bite back like the proverbial snake.

- Spread of jihadi culture.

- Taliban like others has never accepted the Durand Line (renewed demand for Pakhtunistan). It can cause instability as also interfere in China’s handling of Uighurs in Xinjiang, by supporting them (a threat which China takes very seriously).

- Talibanisation of Pakistan.

Indian stakes in Afghanistan are not existential

India too desires Afghanistan aligned to its national interests. The necessity is more due to geography as also the China-Pakistan adversarial collusivity with scope to exploit the violent jihadist elements in Afghanistan using ambiguity as a cover, causing both external and internal instability in India. On a positive note, India can also use its strategic partnership (India-Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement in October 2021) with a stable aligned Afghanistan to leverage geo-political and economic gains and entry into CAR (Central Asian Republics), Iran and onto Middle East and Europe. We are well placed to play a pivotal role (despite being a low-key player so far) to form a consensus on how to shape the future of Afghanistan, which naturally depends on how we handle Taliban.

Iran is wary of elements who are anti-Shia which suits India, as it places Pakistan in the opposite camp. India views Russia as a balancer in the regional security matrix, despite its proximity with China, due to its interests in CAR and Europe. India needs to broaden diplomatic engagement/appoint Special Envoy, and further enhance multi-dimensional assistance.

The Future: Advantage Taliban, but can they close out the match?

The Taliban are not a monolithic organisation or a homogeneous group. The Taliban now have somewhere between 50,000 and 60,000 active fighters and tens of thousands of part-time armed men and facilitators, according to Afghan and American estimates. They are an assortment of groups/clusters; Afghan Taliban is the biggest cluster, and rest are broadly divided into Pashtun, CAR group apart from presence of IS (Khorasan) and Al-Qaida (AQ). “It is a networked insurgency; but very decentralized, and has the ability for the commanders at the district level to mobilise resources, and be able to logistically prepare,” said Timor Sharan, an Afghan researcher and former senior government official[viii].

However, at the top, they gain legitimacy from a single source, a single leader; Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada, commander of the faithful. Taliban political chief Mullah Abdul Ghani Barada, and military chief Mohammad Yaqoob, son of Mullah Omar, the erstwhile spiritual leader of Taliban; form the top leadership.

The Taliban insurgency has also been a unifying cause for some smaller foreign militant groups. Around 20 foreign militant groups are active in Afghanistan, including Pakistani extremist groups like the Pakistani Taliban, Lashkar-e Jhangvi, Lashkar-e Taiba, Jaish-e Muhammad, and Central Asian militant groups including the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), the Islamic Jihad Union, and the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, a militant group fighting for Uyghur independence in China. Some of these groups operate under the Taliban umbrella.

Each of these groups has a unique relationship with the Taliban; operationally, ideologically, or economically. One thing that slowed down the negotiations with the US was that the Taliban’s political leaders wanted to take every small issue down to their commanders, bringing them on board to avoid rebellions and breakaways. They will likely face many of the challenges that once dragged the country into anarchy. The relationship between the political leaders and the military commanders who have monopoly over resources and violence will be tested. The 1990s civil war in Kabul happened not because the political leaders couldn’t agree among each other; it happened because the political leaders could not control the ground commanders, as they were not on the same page.”[ix]

As the Taliban smell victory, it is imperative that they the keep the groups together under one umbrella. The major thing holding the Taliban back at this point is the government’s supremacy of the air and its superior strike forces in the form of commandos and special police units. But those units are being worn down and the Afghan Army has been slowly failing as an institution for the past five years.

Al-Qaeda and IS (Khorasan)

Al-Qaeda is a largely diminished force, with only several hundred fighters in Afghanistan. But it remains a crucial part of the Taliban insurgency. Taliban and Al-Qaida have been long time partners and are co-dependent, according to experts. The IS (Khorasan) group has bases in a few districts of Kunar Province, and they are also likely present in parts of neighboring Nuristan Province, another remote, mountainous province. Reports that IS (Khorasan) militants are active in northern Afghanistan are “unreliable”. The recent arrests of IS (K) fighters and leaders in major urban areas shows that there are still IS (K) “sleeper cells” in the country. Most IS fighters are thought to be former members of Pakistani militant groups, especially the Pakistani Taliban.

Getting Stronger with Political Legitimacy

The new agreement and the looming US exit places the Taliban in the strongest position they have ever been. The Taliban have demonstrated to the Afghan people, the world, and especially militant groups around the world, that they possess the (military) capability to resist a US invasion and outlast a superpower. They have made themselves an intrinsic part of any attempt to find a long-term solution for peace. Adding to the Taliban’s leverage is the political legitimacy it has managed to gain as an international actor; one that the US has negotiated with, and now asking them to be part of an interim Afghan government[x] (and coercing Ghani!).

The Taliban over the years has evolved its relationships with all regional stakeholders barring India. Here too Taliban has shown diplomatic finesse stating that it will not act nor allow any party to act against another country, specifically naming India[xi].

A word of caution: Taliban has always rejected the democratic ideals of universal suffrage, free and fair elections, and respect for minorities, all of which are prerequisites, as outlined in the draft agreement. It has also always considered the ANG (Afghan National Govt) an ‘American puppet’. The Taliban are not pressed for time and can wait until they get what they want: A complete US withdrawal, a slow surrender of democracy, and a return to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan that the group installed and commandeered in Afghanistan from 1996 until losing it to the US invasion in 2001.

The Final Battle for Power

Afghan government forces are in disarray. The Afghan National Army, which is meant to be the country’s backbone of defence, and the blue-uniformed police, which tends to bear the brunt of Taliban attacks, are operating at roughly 50 to 70 percent of their official maximum strength of 352,000, due to a combination of corruption, attrition and difficulty finding replacements. The most effective Afghan units are the special operations forces, which together with the remaining Americans, are holding things together. Yet even the Afghan special operations forces struggle to hold back the Taliban without the help of US advisers and airstrikes. After all, they are up against an enemy that uses suicide car bombs and improvised explosive devices, devastating tools that the Afghan government thankfully does not employ[xii].

In addition to local cadres, the Taliban field special “red units,” or quick reaction forces, that are trained, and are deployed to spearhead major offensives. The Taliban’s recent success on the battlefield will almost certainly motivate the group to fight on. With the South and East Afghanistan already in Taliban control the Government could collapse. It is also possible that the government, its special operations forces, and the old Northern Alliance—Tajik, Hazara, and Uzbek leaders—could muster enough unity and grit to stave off the fall of Kabul.

Indeed, the Northern Alliance is already rumoured to be mobilizing forces to fight. Violence levels and attacks by Taliban on ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces) will escalate once US and NATO finally withdraw. Even given the most optimistic scenario the ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces) may not hold on for long. Forecasting this very volatile geo-political and turbulent scenario is fraught with danger. US is vaguely talking of keeping mobile reserve forces either in bases nearby or even at sea and adopt ‘over the horizon’ counter-terrorism policy; deploying of USS Eisenhower aircraft carrier and Qatar or a CAR (Central Asian Republic) nation as mother base and basing of long range strategic lift aircraft, are being talked off. But will these actions even if executed be able to stave off the inevitable?

The Internal Political Wrangles and Prognosis

Watching the inevitable, recently a fair number of Afghans are now willing to tolerate Taliban rule if it means finally achieving peace. As already discussed, not only will the Afghans and Americans determine the course of the war, but China, India, Iran, and Russia all have interests in Afghanistan and do not wish to see a Taliban Emirate (except Pakistan; China too will exploit its relationship with Pakistan and are getting closer to Taliban leadership).

However, it is unlikely that any of the regional players (certainly not India) will be keen to deploy peace keeping forces in Afghanistan. This has already been vehemently opposed by the Taliban, and was the raison d’etre for Taliban to emerge after the occupation of Afghanistan by USSR, to drive away any foreign forces from Afghanistan.

The current Afghan National Government led by Ashraf Ghani is on a weak footing with internal dissensions and very low credibility with the people. Their intransigence and inflexible approach have worsened the political environment. The rapprochement between Afghan government and Taliban seems even more unlikely and an ‘inclusive interim government’ appears to be a mirage. Neither side wants to compromise as President Ghani feels he is democratically elected leader. Unless the regional players coalesce and act towards peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan setting aside their differences and own aspirations: ‘We are staring at the grim prospect of a civil war’.

[i] Secunder Kermani and Mahfouz Zubaide, Afghanistan:’We have won the war, America has lost’, say Taliban, 15 Apr 21, BBC News

[ii] ‘Three-day Eid ceasefire comes into force in Afghanistan’, 13 May 21, Al Jazeera.

[iii] ‘War in Afghanistan’, Global Conflict Tracker, 28 May 21.

[iv] Carla Babb, ‘US Completes Up to 25% of Afghan Withdrawal’, May 25, 2021, Voice of America.

[v] Missy Ryan and Karen DeYoung, ‘Biden will withdraw all U.S. forces from Afghanistan by Sept. 11, 2021’, 14 Apr 21, The Washington Post.

[vi] Stanley Johny, ‘Explained | Joe Biden’s Afghanistan peace plan’, 10 Mar 21, The Hindu

[vii] Philip Holtmann, ‘Terrorism and Jihad: Differences and Similarities’, Perspectives on Terrorismhttp://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/352/html. Accessed on 10 Apr 21

[viii] Mujib Mashal, ‘How the Taliban Outlasted a Superpower: Tenacity and Carnage’, January 15, 2021

[ix] ibid

[x] Kriti M Shah, ‘The Taliban Play the Waiting Game’, a chapter in essay titled ‘From War to Peace: The Reginal Stakes in Afghanistan’s Future’ compiled by Kabir Taneja, ORF – Issue Briefs and Special Reports, 26 Mar 21, Link – https://www.orfonline.org/research/from-war-to-peace-the-regional-stakes-in-afghanistans-future/. Accessed on 29 May 21

[xii] Carter Malkasian, ‘The Taliban Are Ready to Exploit America’s Exit: What a U.S. Withdrawal Means for Afghanistan’ April 14, 2021