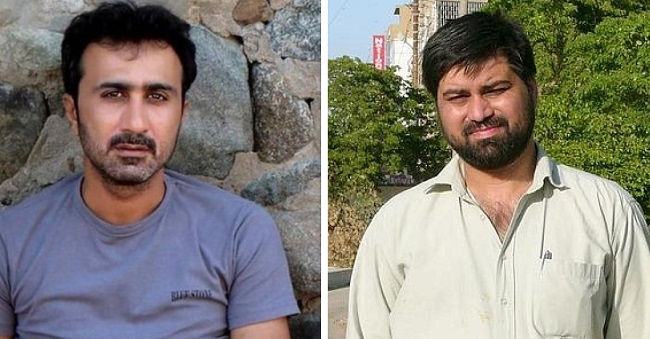

The news of Swedish police recovering the dead body of a 39-year old, Sajid Hussain, a Baloch journalist, outside Uppsala about 60 kilometres north of Stockholm on April 30, brings back a strong sense of déjà vu as one is overwhelmed by bitter memories of another 40-year old Pakistani journalist named Saleem Shahzad whose body was recovered in Punjab province of Pakistan, nine years ago. Whereas it’s incorrect to try and place two different incidents into the same template, but since there are such strong similarities in these two cases, comparison becomes inevitable!

For one, both journalists went missing when they were on their way for some work; while Shahzad was driving down to a TV station for an interview on May 27, 2011, Sajid Hussain had on March 2, 2020 taken a train to Uppsala for collecting the keys of his new apartment there. Secondly, despite both journalists disappearing in broad daylight and that too from busy places, there’s not even a single witness to any of these abductions. Thirdly, the dead bodies of both the journalists were found dumped in water bodies–that of Hussain was fished out from Fyris river near Uppsala, barely 60 km from Stockholm and that of Shahzad from Upper Jhelum canal in Mandi Bahauddin district of Punjab Province in Pakistan.

It can always be argued that the above mentioned similarities mean nothing and one could even mock the same by saying that there’s yet another similarity– that forenames of both the deceased start with the alphabet ‘S’! But the similarity in both these cases goes far beyond cosmetic; there is irrefutable proof that the reportage of both journalists had antagonised Pakistan Army and the ISI. Shahzad wrote extensively on widespread infiltration of jihadis into the armed forces of Pakistan and the nexus between the country’s deep state and terrorist outfits; Sajid Hussain exposed the inhuman ‘kill and dump’ policy being followed by Pakistan Army and ISI in Balochistan. Another similarity was that since both the deceased journalists based their reports on factual details and never retracted their reports, it embarrassed the military and intelligence agencies to no end.

But the most telling similarity was that Sajid Hussain as well as Shahzad had been receiving threats from the ISI and both knew that their lives were in danger. In a piece written for ‘The New Yorker’ (Letter from Islamabad; The Journalist and the Spies, September 19, 2011 Issue), award winning American journalist Dexter Filkins, who had met Shahzad just nine days before his mysterious disappeared writes, “… And then Shahzad changed the subject. What he really wanted to talk about was his own safety. “Look, I’m in danger,” he said. “I’ve got to get out of Pakistan.” He added that he had a wife and three kids, and they weren’t safe, either. He’d been to London recently, and someone there had promised to help him move to England.”

Filkins goes on to recount, “The trouble, he (Shahzad) said, had begun on March 25th, the day that he published the story about bin Laden’s being on the move. The next morning, he got a phone call from an officer at the ISI, summoning him to the agency’s headquarters, in Aabpara, a neighbourhood in eastern Islamabad. When Shahzad showed up, he was met by three ISI officers. The lead man, he said, was a naval officer, Rear Admiral Adnan Nazir, who serves as the head of the ISI’s media division.” Filkins adds, “They were very polite,” Shahzad told me. He glanced over his shoulder. “They don’t shout, they don’t threaten you. This is the way they operate. But they were very angry with me.” The ISI officers asked him to write a second story, retracting the first. He refused.”

However, the scariest part of this report is Shahzad’s account of his previous meeting with ISI officers, five months ago. He told Filkins that “After a tense meeting with two ISI officers about the article (regarding apprehended Taliban commander Abdul Ghani Baradar having been secretly released by ISI), Shahzad called Ali Dayan Hasan, the director of Human Rights Watch in Pakistan. Hasan suggested that Shahzad make notes of the meeting. Shahzad did so, and sent a copy of them to Hasan.

Shahzad wrote that he was met at headquarters by two ISI officials—Commodore Khalid Pervaiz and Rear Admiral Nazir, the same officer who gave him the warning in March. Nazir and Pervaiz were courteous as they asked him to reveal his sources for the Baradar story. Shahzad refused. They asked him to publicly retract the story, and Shahzad refused to do that, too. The ISI officers did not push him, he wrote. But at the very end of the conversation Nazir made an ominous remark. He said, “We recently arrested a terrorist and recovered a lot of data-diaries and other material-during the interrogation. The terrorist had a hit list with him.” He then added, “If I find your name on the list, I will certainly let you know.”

Unfortunately, before he could escape from Pakistan, Shahzad disappeared and his badly battered dead body was recovered subsequently. However, Sajid Hussain was much luckier as he chose to flee the country immediately after his damning reports on ‘forced disappearances’ and rampant human rights violations by the Pakistan Army and ISI in Balochistan resulted in the police raiding his house and interrogating his family members. Working his way through Dubai, Oman and Uganda, Hussain finally reached Sweden and was eventually granted asylum. True to his profession, he continued to highlight the persecution of Balochis by Pakistan’s deep state through ‘Balochistan Times’. So, when he went missing on March 2, the needle of suspicion naturally pointed at the ISI as no one else had anything to gain from his death.

There can be only two explanations for the inability of Swedish police to trace out Hussain for three weeks– one, its lack of professional proficiency, and two, the extraordinary precautions taken by his abductors to avoid detection. Since Swedish police has an impressive track record, one can safely rule out the former possibility. So, it’s quite likely that Hussain’s disappearance is no ordinary kidnapping but a meticulously planned covert mission (which in intelligence parlance is referred to as a ‘snatch operation’) carried out with perfection by an experienced spy agency. But with the Swedish police declaring that “The autopsy has dispelled some of the suspicion that he was the victim of a crime,” it appears that an effort is being made to prepare grounds for declaring this death as an accident or even suicide.

Given the accentuating factors discussed above, ascribing Sajid Hussain’s death to an accident or suicide doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. Sajid Hussain had left by train for Uppsala with the specific purpose of obtaining the keys for his new apartment and not for sightseeing or exploring the riverside. So, since there was no reason for him to have gone anywhere near Fyris river, it’s implausible that he ended up falling into it by accident. As far as the suicide theory goes, why should a man who wishes to end his life take all the trouble to take a 60-km train ride and then jump into a river, when he can find other less agonizing and equally effective ways to end his life while sitting right at home?

Furthermore, if he did intend on committing suicide, then he would have at least left a suicide note for his wife or colleagues– being a journalist, sending a tweet, message or email would be the first thing that would have come to his mind. That’s why the apparent haste being shown by Swedish police only raises more suspicion that there seems to be much more than what meets the eye!

Tailpiece: The coroner’s report on the approximate date and time of Sajid Hussain’s death will provide an important clue– if it emerges that Hussain died 24 hours after going missing, then it’s absolutely clear that there’s some foul play involved. Because a man who’s left his wife aback home and has gone on a trip solely for collecting his apartment keys won’t end up accidentally drowning himself in a river. Similarly, if a man has taken a train ride to reach a pre-decided place where he intends to commit suicide, then he won’t sulk around for 24 hours before plunging into the river.

Dissidents face threat of extinction from the government or deep state of their parent countries and since Sweden is considered a safe place, it’s a popular destination for the persecuted. Sajid Hussain too thought so and that’s why it becomes the moral responsibility of the Swedish government to leave no stone unturned in its efforts to track down his assailants!