Indian policy makers have to ensure that all action taken by other nations are aligned to our national interest. The most important cog in the wheel is Afghanistan. The US will soon exit Afghanistan leaving us to deal with Pak-sponsored mujahedeen and other mercenaries who are now engaged in Afghanistan. The sooner we realise this and prepare for contingencies likely to befall on us after the US pull out, the better it will be.

Politics

makes strange bedfellows while destiny imposes difficult neighborhoods. The two

nation theory being followed by Pakistan survives on spewing venom at its

secular, democratic and economically stronger neighbour — India. Two people of

similar socio-cultural backgrounds, who otherwise would make the best of

friends, have become enemies within the confines of their national boundaries.

Even such Pakistani politicians who are considerably liberal are compelled to

breathe hatred towards India to ensure their political survival.

While

most nations run on policies, Pakistan runs on the diktats of a fundamentalist Mujahedeen-Military

nexus. Here, even eminent non-Muslim personalities are discriminated against

and denied opportunities to rise. The foreign and domestic policies are mostly

formulated in the GHQ or ISI headquarters and passed down to the legislature or

non-state actors for implementation. GHQ (General Headquarters) is the head

office of Pakistan Army and located at Rawalpindi and ISI (Inter-Services

Intelligence) is the intelligence agency of Pakistan.

Although

Pakistan extends lavish receptions to visiting Indian delegations, its actions

on borders and diplomacy leave much to be desired for achieving the envisaged ‘Aman’ (peace). The reasons for Pakistan’s

hatred towards India are manifold but it is mainly due to their failure in

military misadventures against India in the Indo-Pakistan War of 1947 and 1965 and

dismemberment of the nation in Indo-Pakistan War of 1971. These events led to

the creation of Pakistan’s policy of bleeding India through a thousand cuts.

Under this policy, Pakistan diverted US aid for Afghan Mujahedeen to create

unrest in Punjab in late ’70s. The policy fanned the embers of discontent

amongst gullible youth and disgruntled elements of Punjab. Fortunately, good

sense prevailed and the evil plan fell flat with time.

A

bigger impact was witnessed in Jammu and Kashmir, especially the Kashmir Valley.

Having created unrest in the valley, Pakistan realised the idea of its amalgamation

with itself was most appealing. It started sending its unemployed, religiously

indoctrinated and madrassa educated youth to spread greater degree of violence

and unrest in Kashmir Valley, and also propped up a local element named Hizbul

Mujahedeen (HM) for terrorist activities in the name of Jihad (Holy war).

Hizbul

Mujahedeen became the biggest militant group in the valley with Kashmiri leadership

and foreign following. Soon, the battle hardened guest Mujahedeen refused to

play the second fiddle to the soft Kashmiris. During this period the Hizbul Mujahedeen

had several turf skirmishes with other smaller local militant organisations

which were decimated by their overwhelming ferocity of firepower. A worried Pakistan

then propped up several foreign militant dominated organizations with

‘pan–Islamic or Islam sans frontiers’ agenda. These organizations had no

connection with Kashmiris. The locals suffered their wrath but resolutely

rejected their Wahhabi-Salafi diktats to their Sufi ideals. Foreign sponsored

terrorism thus weakened with time.

The

Pakistani agenda has been challenged strongly by India. Though, we may not be

in a position to say that the terrorism/insurgency has ended altogether, it can

be said that the fish is not getting water to swim. We cannot, though, let our

guard down because of the fact that Pakistan is still providing moral, material

and monetary support to the militant outfits like JuD (Jamaat-ud-Dawa), JeM

(Jaish-e-Mohammad) while attempting to prop up HM (Hizbul Mujahedeen) yet again.

In order to win this battle of wills, India, first and foremost needs to become economically sound and militarily even more powerful. Economic strength will lead to development and eradication of poverty and military strength will be a deterrent for others to meddle in our affairs with impunity. Opposing these elements, combined with political will must exhibit the nation’s intent towards not accepting the nonsense perpetrated by Pakistan.

Pakistani

supported separatist jihadist propaganda needs to be countered tooth and nail in

a timely manner, supported by truth, right values and character. Pakistan may

refute our cries for action but the world by now has a clear picture of what

goes on in the dark alleys of Islamabad. If pressure is put, Pakistan may

recoil under shame or international pressure.

Indian policy makers have to ensure that all action taken by other nations are aligned to our national interest. The most important cog in the wheel is Afghanistan. The US will soon exit Afghanistan leaving us to deal with Pak-sponsored mujahedeen and other mercenaries who are now engaged in Afghanistan. The sooner we realise this and prepare for contingencies likely to befall on us after the US pull out, the better it will be. The Pakistan-based militant warlords aligned against India like Syed Salahuddin, Hafiz Saeed and Masood Azar are already preparing to revive terrorism in Kashmir. These developments should be considered serious and seen in the light of likely ISI promises of enhanced weapon and narco-dollars support to mullah-militant nexus.

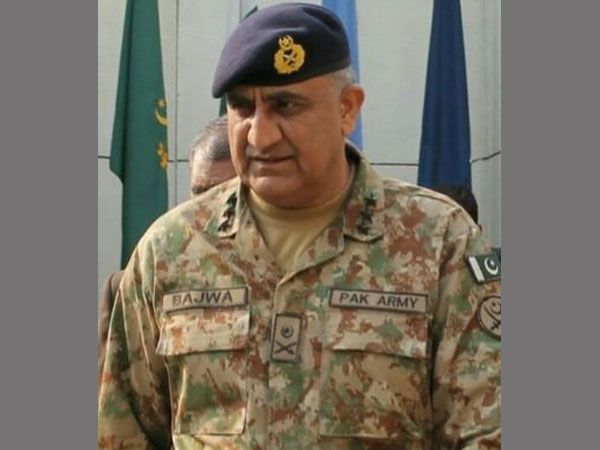

Historical

perspective indicates military control of civilian institutions in Pakistan. Most

of Pakistan’s military dictators have, at some point in time, been protégés of

the government of the day. Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Since independence, Pakistan has endured more than half of the period under

military dictators. India needs to remain sensitive of this reality and

prepared for any misadventure that the Pakistan Army, if cornered, will chance

upon.

We

have to guard against petty internal issues taking larger form and vote bank

politics in the backdrop of emerging security threats to democracy and larger

national interest. Calls for plebiscite in the historical and present

perspective is inconsequential and airing such thoughts will not bring about

conditions for the same.

Merely

parroting for the repeal of AFSPA (Armed Forces Special Powers Acts) when the

same is not in democracy and is in national interest would be a waste of energy.

Its repeal will force Army and Paramilitaries to barracks giving free run to

jihadists to enter porous hilly forested Line Of Control (LOC) through

their training camps in Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK) from the 100

reported launch pads. Had the state forces of Jammu and Kashmir, with due

regards to them, been able to handle such situation in 1989, Kashmir would have

been a real paradise which the peopleseek

today. Unfortunately, coping with crime is a different ballgame from combating

terrorism.

The

‘Aawam’ (people) of Kashmir is hungry

for security, peace, development, good governance, corruption free society, two

square meals, freedom from daily worries and equality of all. Society and

nation should draw its strength from patriotism, articulate values and

character.