OP Chautala’s release plea is a classic case of damned if you do and damned if you don’t for the Delhi’s AAP government. Political analysts believe that whether Arvind Kejriwal’s AAP recommends release, or the detention of OP Chautala, there will always be a political risk to AAP-JJP alliance in the state of Haryana.

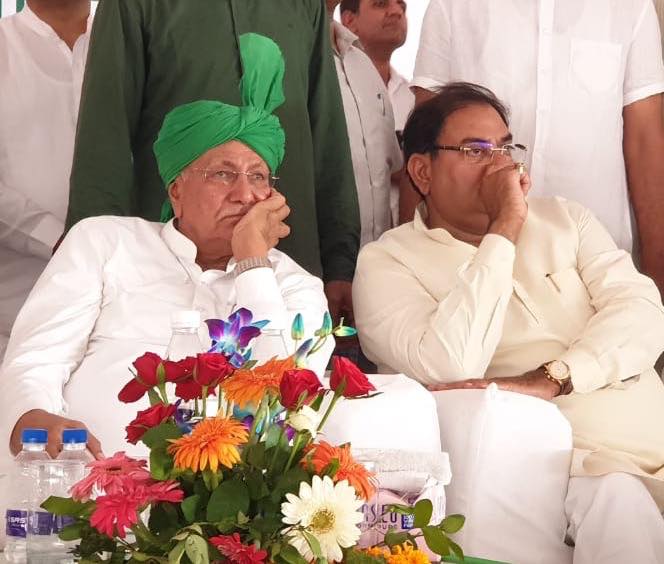

Former Haryana Chief Minister Om Prakash Chautala’s application in the Delhi High Court for his early release from jail has put the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) in a dilemma. OP Chautala, 83, who is serving a 10-year jail term in Haryana’s JBT (junior basic trained) Teachers’ Recruitment Scam along with his elder son Ajay Singh Chautala and 53 others, had approached the Delhi High Court on February 19, 2019 to seek directions for his release from prison in accordance with the Union government’s remission policy of July 18, 2018. This policy giving special remission to certain categories. While hearing this case, the Delhi High Court bench consisting of Justices Siddharth Mridul and Pareek Jalan asked Delhi’s AAP government to decide the premature release plea of Chautala within four weeks.

Chautala has contended that keeping in mind his 83 years age, disability and the period of seven years (out of ten) that he has already spent in jail, his premature release application may be considered.

Delhi government’s counsel Rahul Mehra opposed Chautala’s plea on the ground that he (Chautala) was convicted for corruption which was a serious offence.

But Chautala’s advocate Amit Sahni pleaded: “Chautala was convicted for 10 years under the Indian Penal Code and 7 years under the Prevention of Corruption Act. He has already undergone the sentence awarded under the Prevention of Corruption Act and also has a permanent disability of 60% (as on April 2013) and later has undergone implantation of pacemaker in June 2013. The disability is progressive and at present it is more than 70% and he fulfills the conditions laid in two clauses of the said notification. His age is 83, which itself is sufficient to consider releasing him by giving benefit of the notification.”

OP Chautala’s release plea is a classic case of damned if you do and damned if you don’t for the Delhi’s AAP government. Arvind Kejriwal-led AAP was hopeful of a tie-up with recently floated Jannayak Janta Party (JJP). The political outfit JJP has been formed by OP Chautala’s own grandsons who, ironically, are opposed to his own INLD (Indian National Lok Dal).

Political analysts believe that whether Arvind Kejriwal’s AAP recommends release or the detention of OP Chautala, there will always be a political risk to AAP-JJP alliance in the state of Haryana. If Delhi government gives positive recommendations and Chautala gets out of jail, he will certainly re-energize the sagging spirits of Indian National Lok Dal (INLD) and galvanize its workers which will mar the winning chances of AAP-JJP alliance in Haryana.

However, if Arvind Kejriwal’s government turns down the release plea, it will undoubtedly create anger and resentment towards AAP-JJP political alliance and result in a sympathy wave for INLD among Jat voters of Haryana. Already there’s resentment in rural areas against the Delhi government’s alleged decision to obstruct Chautala’s furlough application which became evident during Jind by-elections on January 28, 2019. The by-elections saw mass transfer of INLD votes to the BJP to obstruct AAP-JJP alliance from winning. The AAP-JJP candidate Digvijay Singh Chautala, a rebel from INLD lost the Jind by-elections decisively.

AAP’s decision to turn down OP Chautala’s release plea will also force the INLD leadership to forge a tie-up with BJP or in case of a failure of any alliance with BJP, they may again motivate INLD voters to transfer their votes to BJP instead of supporting the AAP-JJP combine.

The INLD party leaders had publicised during Jind by-elections that AAP-JJP alliance had obstructed the furlough of their ex-Chief Minister of Haryana O P Chautala to keep him away from the elections. They alleged that initially, the INLD chief was to be released on furlough on January 22, ahead of Jind by-poll. However, the release was postponed to January 29, that is, after the elections with the condition that he shall not attend any political meeting and shall not indulge in political activities during the period of furlough.

Attacking the JJP and AAP and accusing the former Haryana Chief Minister O P Chautala’s own grandson, Member of Parliament Dushyant Chautala, of back stabbing his own grandfather the state INLD president Ashok Arora had alleged, “It is clear that AAP government in Delhi along with Dushyant and Digvijay have played a role in denial of furlough. They have stooped to a new low by doing this.”

Political pundits of Haryana are convinced that whatever maybe Arvind Kejriwal-led AAP’s decision about early release of OP Chautala, it will surely have a long term impact on INLD and also on AAP-JJP alliance future in Haryana.

What is the Union government’s Remission Policy of July 18, 2018?

As part of commemoration of 150th Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, the following categories of prisoners will be considered for special remission and released in three phases.

(a) Women convicts of 55 years of age and above, who have completed 50% of their actual sentence period.

(b) Transgender convicts of 55 years of age and above, who have completed 50% of their actual sentence period.

(c) Male convicts of 60 years of age and above, who have completed 50% of their actual sentence period.

(d) Physically challenged/disabled convicts with 70% disability and more who have completed 50% of their actual sentence period.

(e) Terminally ill convicts.

(f) Convicted prisoners who have completed two-third (66%) of their actual sentence period.

Special remission will not be given to prisoners who have been convicted for an offence for which the sentence is — sentence of death or where death sentence has been commuted to life imprisonment; cases of convicts involved in serious and heinous crimes like dowry death, rape, human trafficking and convicted under POTA, UAPA, TADA, FICN, POCSO Act, Money Laundering, FEMA, NDPS, Prevention of Corruption Act, etc.

In Phase-l, the prisoners will be released on 2nd October, 2018 (Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi), in Phase-ll prisoners will be released on 10th April, 2019 (Anniversary of Champaran Satyagrah) and in Phase-Ill, prisoners will be released on 2nd October 2019 (Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi).