The outright sale of India’s most iconic club, Mohun Bagan, happened around the time a Bengali novel on aspirations of a football coach hit the stands in Kolkata. Probably it was a mere coincidence but what is interesting is that both, the sale of the club and the launch of the novel, had a tinge of sadness, a mood of realism.

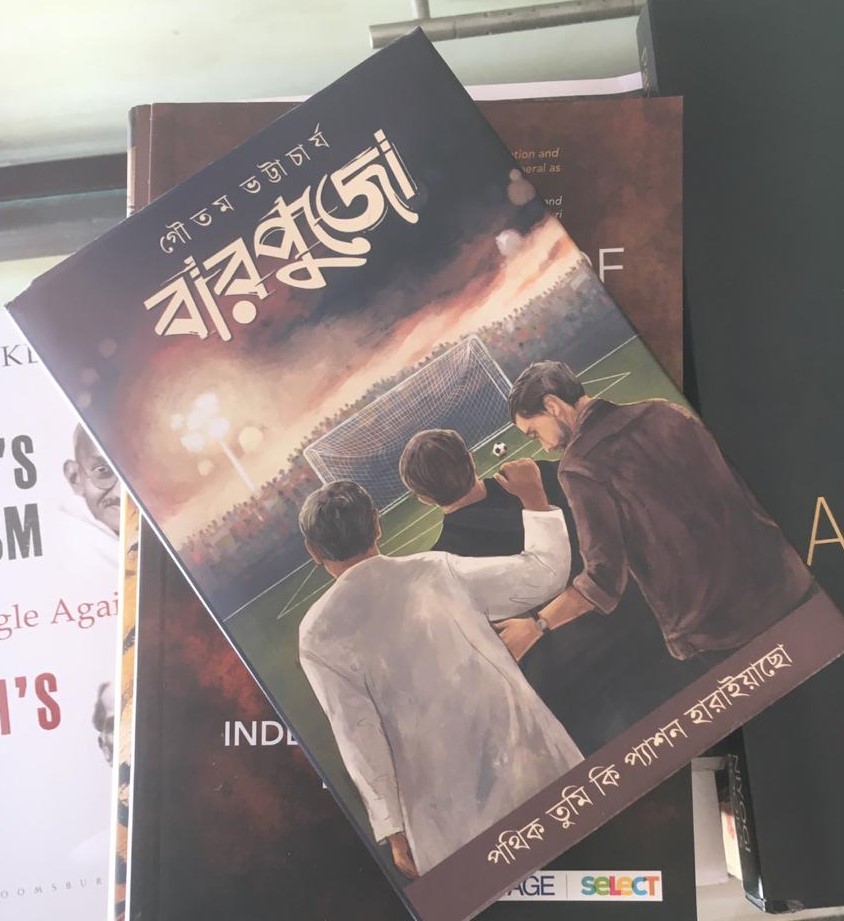

Kolkata-based RPG-Sanjiv Goenka Group bought out Bagan in a hush-hush deal, triggering vociferous reactions from supporters across the globe. Group CEO Sanjiv Goenka said the club was acquired to push the group’s sporting ambitions. At the same time, footballers, actors and politicians started promoting seasoned journalist and anchor Gautam Bhattacharya’s book, Bar Pujo, which translates into worshiping the goalposts. It is a strange and unique Bengali custom where priests offer prayers to goalposts on the first day of the Bengali New Year — always in mid-April — and seek sporting success.

Interestingly, both the book and the sale of Mohun Bagan once again brought the fading fortunes of the Kolkata soccer clubs together in limelight. The book, written in Bengali language, triggered debates across colleges, clubs, and coffee stores about what would save football clubs of Kolkata: Passion, or cash? Or both?

So let’s talk about the novel first.

Protagonist Archit Mukherjee is a soccer coach who does a decent job with the Tatas — a dream for many in Kolkata — and wants a team that should be Kolkata’s answer to a top English Premier League club, say Manchester United or Liverpool. He is aware of the standards of the game in the city, and in the country. He is very, very realistic. He remembers India last won a decent soccer trophy in 1974 when the nation was crowned joint champions with Iran in U-20 Asia and thereafter it has been a long, long slide. But he still wants parents to push their children to play soccer but not hate cricket because Saurav Ganguly is the state’s biggest icon. More importantly, he wants the passion that was in existence in the 70s to return to Kolkata’s vast green cover — its called Maidan that translates into a big field — and the clubs to regain glory and help the city regain the title of Mecca of Indian football. But the coach is not day-dreaming, he knows India is ranked 108 out of 210 nations by FIFA and an unlikely destination for aspiring footballers. So the local youngsters give football a miss in Kolkata but a steady stream of young men from West Africa and parts of Asia keep landing in the eastern Indian metropolis, hoping Kolkata will be the first step on the road to football stardom.

Mukherjee knows he has a long way to go.

Mukherjee wants — the book claims repeatedly — the passion to grow, he wants the rise of the youth power. His example of passion is not only limited to footballers, it is for all those who love the game. For him, this very passion could exist even in a gatekeeper punching tickets for entry to the stadium. The book has an interesting incident about how one lanky gatekeeper, Hituda to many, found a person coming late for an East Bengal match and asked him the reason. The person, a diehard fan, said he was coming straight from the crematorium after completing the last rites of his son. Mukherjee seeks similar passion from everyone. For him, passion is the way forward.

Mukherjee knows he is Ekalavya, smarter and faster than Arjuna. Like the proverbial story of the epic Mahabharata and Guru Dronacharya seeking a finger of Ekalavya to slow down his fiery arrows and please Arjuna, Mukherjee knows he has to fight alone, he will not have too many big guns on his side. He, only he, must find a way out of the Chakravyuha, or the Circle Of Death. But Mukherjee is not old fashioned, he is the modern Ekalavya who will not sacrifice his finger because he knows the Guru is biased. Mukherjee wants to rule with modern understanding of the game, he wants to walk into a supermarket knowing well what he will buy and then cook a meal and serve. He wants to have the power of Sir Alex Ferguson, he will ignore the star status of his footballers. Yet, he will plug them all over the media. He understands the importance of social media, he knows if a top corporate acquires a club it will run on cash and carry and not only on emotions. Mukherjee is a thinking coach, like a seasoned director, he knows. He also knows the importance of social media’s impact on the game. He is the master chef.

This is not a hop-skip-jump novel, it is brilliantly crafted, very, very nostalgic for those who followed Kolkata football because there are similar examples of such coaches in the city who live with their hopes, ambitions and pains. The author is clear that only the coach knows how a victory is rarely credited to him, it is almost like getting the smallest slice of a birthday cake. The rest is always reserved for the captain, players and team management. The coach is a lone ranger, a silent observer, the boy on the burning deck.

The author reflects on the life and times of successful coaches, failed coaches. In some ways it reflects the life and times of men and women of his profession, journalists. Bhattacharya’s words about a tired coach walking with a huge sports bag can easily be turned into a tired journalist walking home after arguing unsuccessfully with his editor over whether or not to write a big scandal involving a corporate giant. Mukherjee knows he cannot leave the game, he has to be a part of the system to change the system. And change is inevitable. He knows he will only be worshipped if he is successful. Past and failures are rarely remembered.

Like it happened when Mohun Bagan got sold, the incident triggered breaking headlines even as the Department of Posts and Telegraph issued a postage stamp for Parimal “Chuni” Goswami, former Mohun Bagan captain and top footballer who had once turned down an offer from Tottenham Hotspur to spend his entire footballing career at Mohun Bagan. It was all about passion for Goswami, who recently completed 82 years. But very few linked Goswami’s sacrifice to the sale of the club. Arguments still continued, there were some in Kolkata for whom Mohun Bagan was national pride because it was the first Indian club to defeat a British team to win the IFA Shield in 1911. The victory was seen as a path-breaking win against the British rulers of the subcontinent. But the novel also reminded us that the victory was 108 years ago, around the time British royal rulers came to India to kill tigers. I have a feeling the novel reflected the writing on the wall, highlighting the change that many claimed was inevitable in Kolkata’s football clubs. Actually, it reminded football fans in Kolkata that in the new financial year, Mohun Bagan could even have a new name and a new jersey. In short, age-old sentiments will have to take a break. From now on, wealth and heritage will have to walk hand-in-hand, side-by-side.

Mukherjee knew what will be the new heartbeat of Indian football, even though he wept silently in his heart because he wanted a rerun of the glorious 70s. He would be very happy to retain the heritage but knows with changing times, he has to blow with the wind. So the protagonist of the novel keeps his passion intact, thinks about football even from a hospital where he is being treated for low blood pressure following the death of a close friend. Mukherjee lives for another day, another life, and another match. His team wins the trophy riding on the players’ passion.

Football has died many deaths in Kolkata, only to rise like the proverbial Phoenix. An East Bengal-Mohun Bagan match gets no advertisements but over a lakh of supporters without the hype of pink balls and pink coloured lights created to generate crowd at cricket stadiums. There are no big anchors, no great commentary, no cheerleaders, no nothing. But there is passion, there is a deafening roar every time a top club scores a goal. Bhattacharya has talked about this very passion that draws people to such matches. Many know how football clubs are run in Kolkata: Players are rarely paid on time, club owners struggle hard to find players from distant Africa, Spain or Latvia. There are times when the clubs non-playing staff go home without paychecks. Lack of cash means the players will not give their best during a match, it is almost like no hot water in the showers after training. In such cases, only passion works. Just pure, unadulterated passion.

Bar Pujo has reminded many in Kolkata to think about football, and think passionately.