Mohan Guruswamy, fondly called India’s Benjamin Button, reminded India it is time the nation celebrates its greatest military victory after World WarII – the war against Pakistan in 1971 and the birth of Bangladesh.

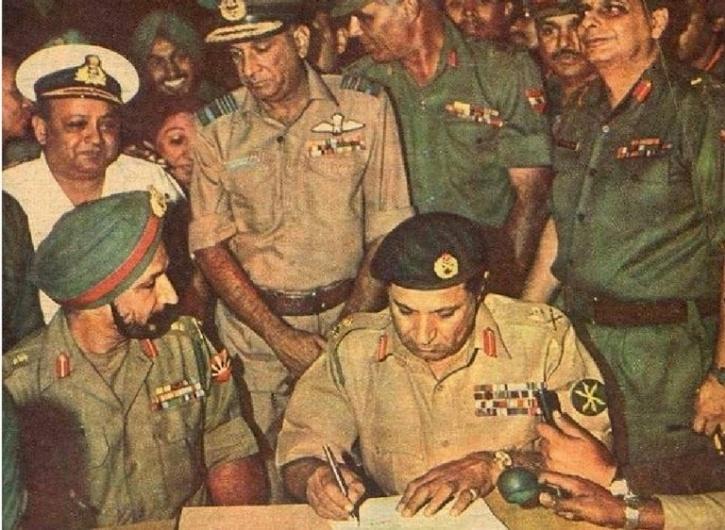

Guruswamy wrote on December 16, 2019, on Facebook, around the time boisterous students took to streets across India to fight cops and protest against what many claim is the contentious Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). he said India lost an estimated 3400 soldiers, and another 4,000 were wounded in the war against Pakistan. India took 93,000 prisoners, very few know that the rifle and bayonet at the Amar Jawan memorial – many call it the India Gate memorial – in the heart of the Indian Capital belong to an unknown Indian soldier who died in Jessore town that lies close to the Bangladesh border in Bengal. It was 48 years ago, India under Indira Gandhi displayed courage and defied both Washington – then ruled by US President Richard M Nixon and the UN – and led India to its greatest victory in less than a fortnight. Atal Behari Vajpayee called her a Durga, the ten hand goddess who rides a tiger and slays demons. Strangely, very few in India remember Vijay Diwas. At an internal class XII examination in the Indian Capital, students drew blank — nearly 98% in the class — when asked about Vijay Diwas.

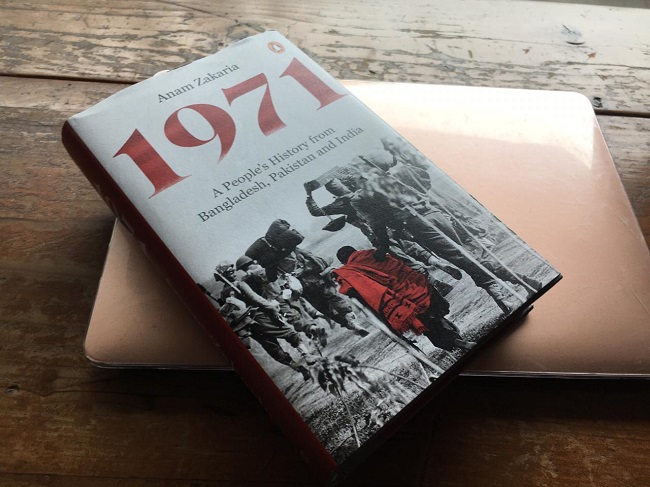

And now, Anam Zakaria’s brilliantly researched book, appropriately titled 1971, has hit the stands and offers a great opportunity for many to revisit those days of blood, horror and death, mostly in the country’s eastern sector. The book will help Indians understand how the war was fought and eventually won. Zakaria writes how Indian soldiers fought a two-front conventional military engagement under the leadership of the redoubtable Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw. And let’s not forget, reminds Zakaria, how Manekshaw staved off repeated demands for an immediate war in early 1971 despite the situation turning very, very tense and grim in East Pakistan. The big boss of the Indian Army reminded politicians of his demand for more cash for defence and argued a war in the summer of April and May will destroy all standing wheat crop in Western India and the nation could plunge into a food crisis and that a war in June-August would cause trouble for moving troops due to floods in Eastern India and East Pakistan. The war finally broke out on December 3, 1971.

Manekshaw’s restraint worked, the book explains how, India gained both tactical advantage and was able to explain to the world the situation in East Pakistan where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, father of the current Bangladesh PM Sheikh Hasina Wajed, was illegally denied his electoral victory in 1970 by Pakistan’s ruling coterie influenced by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Thanks to interviews Zakaria conducted with witnesses and victims, the book explains how the crisis hit a point of no return in March 1971. The Pakistan Army unleashed a reign of terror on the hapless Bengalis, an estimated one million crossed over to Bengal. The eventual figure is over 10 million, the influx denting the economy of the state beyond control.

I remembered having read a British Broadcasting Corporation report on an article that was published on June 13, 1971 in UK’s Sunday Times exposing the brutality of the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan. The Sunday Times copy – written by Anthony Mascarenhas – was described by the BBC as one of the most influential pieces of South Asian journalism of the past half century. The Bangladesh government says an estimated three million lost their lives. And there’s little doubt, claimed the BBC, that Mascarenhas’ reportage played its part in ending the war, helped turn world opinion against Pakistan and encouraged India to play a decisive role.

Zakaria’s book needs to be read in the same perspective because she travelled both to Lahore and Dhaka to understand the impact of the war. This is a brilliant effort, unlike those who write it from the eyes of either Dhaka or Islamabad and mess up the whole narrative. I liked the chapter when Zakaria brilliantly interviews students and asks them about the war and those deaths. All remembered, it seemed (to me) many wanted to move on in life because the war was nearly five decades old and that some were . Some in Bangladesh even discussed cricket and blamed India for being arrogant, and denying Bangladesh waters of the Teesta river. Some even blamed India (read BCCI) for not allowing Indian cricketers play in the Bangladesh cricket leagues. Time and again in the book the author displayed her grasp over the subject, I have a feeling it helped her because she was born and groomed in Lahore and understood the sensitivities of the people of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Zakaria worked like a very good reporter.

Many Zakaria interviewed for the book admitted that the conflict was sparked by elections, which were won by the Awami League, an East Pakistani party, which wanted greater autonomy for the region. The book also highlights a very important fact: That many Bengalis were convinced that West Pakistan was deliberately blocking their ambitions. The Army launched a pre-emptive strike against the Awami League on March 25, 1971. Some of the supporters of the Awami League, the country’s intelligentsia and the Hindu community – it made up about 20 percent of the province’s 75 million people – were also targeted.

One of the fascinating chapters of the book is the one titled Pakistan’s War where the author combines grit, determination and knowledge to pen reactions of those who followed the war as civilians and also members of the Pakistani army. For an author it’s important to dig. I liked her interview with an army major who said something interesting, and something that flows much against the tide. That the first fireworks started when the Mukti Bahini opened fire on the soldiers from the Jagannath Hall of the Dhaka University and then, in retaliation, the soldiers opened fire which was “excessive”. And then, the retired major told Zakaria: “The firing had to be excessive under those circumstances.”

If the book is about war, both sides must find mention.

I think it would be a great project if Zakaria travels through the Jessore road once again and reaches the crowded Bangladesh city. She could do a great film on what could be called The Journey In Reverse. Let this book be a standard manual in all Indian universities. All we need is to get some Vice Chancellors push their pens and open files so that the students can also read this very, very brilliant book.