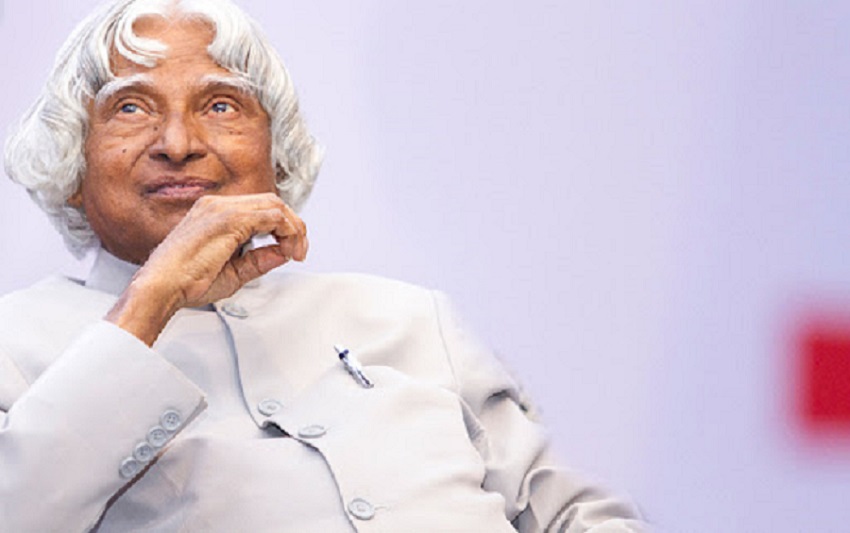

“Transforming the nation into a developed country, five areas in combination have been identified based on India’s core competence, natural resources and talented manpower for integrated action to double the growth rate of GDP and realize the Vision of Developed India” that was former President of India Dr APJ Abdul Kalam’s vision for India by 2020. In 1998, Kalam and YS Rajan, also a government scientist, co-authored a book called India 2020: A Vision for the New Millennium. The book had a simple message: “A developed India, by 2020 or even earlier is not a dream. It need not even be a mere aspiration in the minds of many Indians. It is a mission we can all take up and accomplish.”

“Seldom does one, in these troubled times, see such a lucid marshaling of facts and figures to bolster the thesis that India is mere two decades away from superpower status,” wrote the Times of India at that time while introducing “India 2020.”

Collective delusion, and not critical analysis, has been the hallmark of our media, intellectuals and patriotic elites, then and now — when the missile man envisioned a ‘developed’ India by 2020 then or when our beloved leader tells now that 21st century belongs to India.

Much of the Kalam’s book is a compilation of optimistic forecasts, powered by an impressionable sense of patriotism than by any empirical data. In many ways, the book’s style and substance is an inspiration and precursor to the millions of patriotic messages flooding our WhatsApp Universities of today.

The Vision is dedicated to a ten year old girl whom Kalam met during one of his talks and asked her about her ambitions, to which the young girl replied, “I want to live in a developed India.” The book examines the weaknesses and strengths of India and offers a vision of how India can emerge to be among the world’s top four economic powers by the year 2020. The world’s GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is $91.98 trillion in 2020. India is ranked at No. 7 with a nominal GDP of $2.72 trillion or about 3% of world GDP. In comparison, China is ranked at No. 2 with a nominal GDP of $13.4 trillion or about 15% of world’s GDP. China has left India way behind, breathing down the neck of USA to snatch the No. 1 trophy from it. India is just competing with small European countries like Italy, France or UK in terms of GDP. India is ranked at 145th position in terms of per capita income. India’s nominal per capita income at $2,199 in 2019 was approximately five times lower than world’s average of $11,673. Given that we are now in 2020, we know that India has not become a developed nation — not by a long shot — even before the virus has turned 2020 into a nightmare for the Indian economy.

Dr Kalam and Rajan, assume in the book that there is a “greater likelihood of more women taking part in direct economic activities” and, most incredibly, that “there are good chances that poverty can be fully eliminated by 2007-08.” It is apparent that even after 12 years from the target year of 2008, poverty in India has not been eliminated. The humanitarian crisis posed by the migrant labourers during the lockdown period is a true commentary on the worsening position of poor in India. While making the predictions about more women participation in the economic activities, Kalam and Rajan seemed to have under estimated the deep rooted strength of Indian patriarchy. India’s female labour force participation rate had fallen to a historic low of 23.3% in 2017-18. Only nine countries across the world, including Syria and Iraq, have a lower female participation rate than India’s.

In order to realize the vision of India becoming a developed country by 2020, Dr Kalam and Rajan had envisaged that we need to transform India in five areas where the country has core competence: Agriculture & Food Processing, Education & Healthcare, Information & Communication Technology, Infrastructure Development & Self-Reliance in Critical Technologies. Though India has made substantial progress in Information and Communication Technology and some progress in Infrastructure Development, it could not usher in any transformational change in the Agriculture sector. Inclusive and affordable Education and Healthcare are a mirage. Dr Kalam’s dream of ‘assurance of education on merit with complete disregard to societal and economic status’ is miles away from the bitter reality such that quality higher education is accessible only to rich and not to the poor or not even to the middle classes. Self-reliance in Critical Technologies is still a distant dream. A report by IBM Institute of Business Value and Oxford Economics found that 90 % of Indian Startups fail in their first five years of running.

Vision 2020 assumes that the urban-rural divide will be bridged and the differences of caste, class, religion, language and region will be seen as irrelevant leading to a more united and secular country. In today’s India, these fault lines manifest more than ever since country’s independence.

In spite of the fact that Kalam’s superpower India 2020 prediction was widely off the mark, its spirit continues to survive, with only extension of the target year. During the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, BJP promised voters that India would become a superpower by 2024 if Narendra Modi was voted back as prime minister. There are real costs to the Indian economy associated with living in this “Superpower 2020” dream, of faulty policy making based on unachievable targets. Now, economists like Amartya Sen are showing the mirror that India is in fact losing out even to its South Asian neighbors such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, who are able to offer their people better standards of living.

“To achieve the progress, he envisioned in Vision 2020, that the country’s growth rate must be 10% for 10 continuous years in agriculture, manufacturing, industry and energy sector. So far, the country has never seen this. Maybe we’ve achieved 8% to 9% growth for three years straight, but then it dipped later. India should not work on extractive policy based on tax collection but instead work on inclusive policies, governance and institutions. Instead of relying on tax collections, we must work on developing infrastructure. Only then we can succeed,” Dr APJ Abdul Kalam’s former scientific advisor V Ponraj had said in 2019.