It was in September last year when Enforcement Directorate told the Delhi High Court that the “money trail (in a laundering case) is directly related to Robert Vadra. “There is a money trail directly related to Robert Vadra. Direct payments were made into Pilatus,” said ED counsel DP Singh before a single judge bench presided by Justice Chandra Shekhar. The court was hearing the petition filed by the agency seeking cancellation of bail granted to Vadra in the money laundering case related to the purchase of 75 Pilatus aircraft by the UPA government in 2009-10. The ED claimed to have tracked kickbacks of Rs 310 crore allegedly paid to Bhandari for swinging the Rs 2,900 crore deal. After the AgustaWestland VVIP chopper deal, this was the second big defence contract signed by the UPA government which is being probed by the ED and the CBI. Now, the ED action against Bhandari was politically significant because of his alleged proximity to Congress leader Priyanka Vadra’s spouse Robert Vadra.

So what did the ED claim?

The ED said it found huge cash deposits in Vadra’s front entity in Dubai which were used to acquire properties in London, which linked Vadra to Bhandari. The email correspondence between Sanjay Bhandari, Summit Chadha (London-based relative of Bhandari), Manoj Arora and Vadra showed that he (Vadra) had a keen interest in this property and was interested in knowing all about the renovation work that was being carried out. The ED further informed the court about properties whose beneficial owner was Vadra, this included two houses in London worth 5 million pounds, 4 million pounds and six flats.

The Pilatus case showed the clout and power of Vadra. Everyone in Delhi and other Indian cities knew his prowess, and also the fact that he was fiercely guarded by the powers that be in the Indian Capital. He was like a champion without winning medals. It was only when the BJP-led NDA government returned to power in 2014, his special no-security-check status was withdrawn from the airports. More importantly, he was being treated like the rest, he was no VVIP.

But if you want more then you must rummage through the papers in the state departments of Haryana where the government has begun the process of cancelling the licence given to Vadra’s Sky Light Hospitality to develop land that was later transferred to realty major DLF for ₹58 crore. The Director of the state’s Town and Country Planning Department KM Pandurang is on the record saying the procedural formalities to cancel the licence have been completed keeping in with provisions of the Haryana Development and Regulation and Urban Areas Act, 1975.

Two incidents here highlight the immense power and clout Vadra had during the two terms of the UPA government. The trial is on for the Pilatus case, but the land issue in Haryana only happened because an honest IAS officer decided to stand up and take notice against what he felt was rampant corruption, aided by dubious politicians of the ruling dispensation in Haryana.

What is actually interesting is that the 1991 batch IAS officer Ashok Khemka had shot to limelight in 2012 when he cancelled the mutation of the land deal between Skylight Hospitality and DLF. In 2011, the then Haryana CM Bhupinder Singh Hooda said the licence for the land in Gurgaon’s Sector 83 which was sold to Skylight Hospitality and then transferred to DLF was “deemed to have lapsed”. The licence for the land parcel had not been renewed, Hooda had then said. For the records, the BJP had alleged there were irregularities in the land deal involving Vadra during the term of the Bhupinder Singh Hooda government in the state.

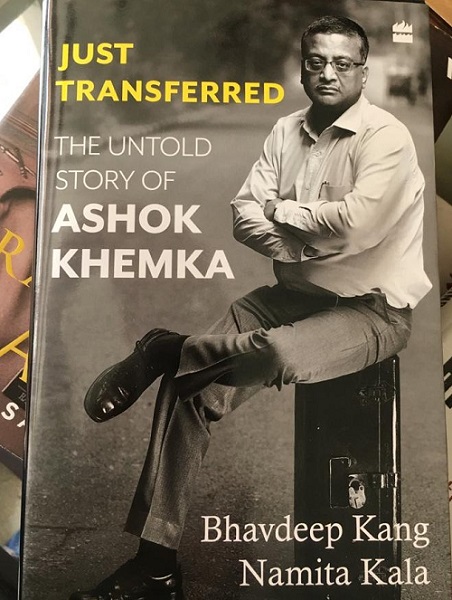

Bhavdeep Kang and Namita Kala’s brilliantly scripted book, Just Transferred: The Untold Story of Ashok Khemka (from Harper Collins) highlights the plight of this brilliant IAS officer who was routinely transferred because he took on the power, the power brokers and politicians. He never protested, no one bothered when he packed his bags and went for the next posting. Worse, messages reached his new office even before he could assume charge, the lobbyists informed the officers that a troublesome person is coming to take charge, he must be listened but ignored. But Khemka stood his ground, he was like the master of the earth, a root man who would not let anything spoil the land. But he was a lone ranger.

When ‘Vadragate’ broke, Khemka was DG, Land Records & Consolidation and Inspector General, Registration and fully aware that manipulation of revenue norms for the benefit of influential individuals was standard practice in Haryana. He had already inquired into and taken action in multiple instances of misappropriation of panchayat land. All hell broke loose, news reports suggested there was evidence of gross undervaluation of properties registered by Vadra’s companies. Khemka started probing his own officers. He asked revenue officials in Gurgaon, Faridabad, Mewat and Palwal to examine the allegations of undervaluation in Vadra’s deals and demanded the relevant land records. But there was a deathly silence.

The book says it all, especially how Khemka reiterated his request for the records. One of the officials got back to him a couple of days later, expressing strong reservations about complying with his request. The official and his colleagues were warned by powerful politicians that the matter should not be probed. Khemka was flummoxed but he brushed his fears aside and renewed his request for the records in question. On October 8, 2011, his staff prepared the paperwork for an inquiry into Vadra’s land purchases in Haryana. Khemka knew he was walking into a lion’s den and there could be some serious, inevitable consequences. He was summoned by the CM on October 11 and ridiculed like anything. He was called Khoparchand that translates into a buffoon. But within seconds, the CM retracted his word. He said, “I am just joking. It is Haryanvi slang.”

Like a James Hadley Chase novel, the authors weave the narrative in a gripping style. Khemka walked back home, realising he would soon be punished by the powerful politicians who would push him out with a routine transfer and loads of humiliation. He was ready. Inevitably, worse followed: He was to be shunted to an under-secretary level post in the Haryana Seeds Development Corporation (HSDC). With a seniority of twenty-two years, he was clearly qualified for a better post, befitting his rank. Khemka raised the red flag and registered his protest, but later that night, at 10 PM, the transfer order was delivered to his home. It was an error of judgement that was to cost Hooda dearly in the days to come, because Khemka’s stint in HSDC would lead to the unearthing of the Raxil scam which would result in a CBI investigation. But Khemka has to leave for a new posting, a new day.

Can you ever imagine the plight of an honest officer who has to face such humiliation for standing tall, standing correct? And what if he buckled and cleared the files. An investigation five or ten years later would push him to humiliation, even behind the bars. Remember the plight of those IAS officers who got caught for no fault of theirs in the infamous coal block allocation scam –the Coalgate? They are still struggling to keep their names clean.

Khemka knew, claim the authors, he had no one to back him. But he was supremely confident because he was honest, downright honest. Those who are honest have no one to fear, not even the Gods. Wrote the authors: “On the morning of 12th October, 2012, a Friday, Khemka followed protocol by calling up the incumbent MD of the HSDC, a promotee and twelve years his junior. He asked his successor when he should take charge. The gentleman was on tour in Rewari, and suggested that they swap jobs on Monday, after the weekend. Khemka informed the office of the chief secretary of the conversation. And off he went to his old office. The news dominating the day was a press conference by the former CM, Om Prakash Chautala, who alleged that Real Earth Estate Pvt. Ltd, a firm owned by Vadra, had bought 29 acres of land in Mewat at a price far below the collector rate. Chautala demanded a probe into Vadra’s dealings in Haryana and alleged undervaluation of registered sale deeds.

Then, he shot off a letter to the chief secretary protesting against his transfer.

At noon, one of his subordinates dropped in to see him. The man’s main agenda pertained to a departmental inquiry against him. He wanted Khemka to undertake it. ‘Sir’ told him that it was no longer possible because he had been transferred, but he promised to write an explanatory note for his successor. They chatted and that’s when Khemka learnt about the size of Robert Vadra’s deal with DLF in Shikohpur village. Vadra had sold his land to DLF on 18th September 2012. Judging from the size of the deal, said his subordinate, the land was worth “16 crore an acre”.

“No, no! I am telling the truth, sir,” the subordinate protested. He went on to suggest that if someone were to purchase two half-acre plots in Shikohpur village, where consolidation was underway, he could ensure the allotment of a 1-acre plot adjoining Vadra’s. Would ‘sir’ know of anyone who might be interested in such a deal? Khemka shook his head dismissively. But on his way out, the functionary decided to drop a copy of the Vadra-DLF sale deed in his superior’s car. When Khemka got home, his man Friday, as usual, piled all the files and sundry papers he had found in the car next to the bed. Right on top was the Vadra-DLF sale deed. The name ‘Skylight’ caught Khemka’s eye. He picked up the document and started reading. As Khemka read the sale deed, it became clear to him that Vadra had earned super profits through what appeared to be a chain of suspicious transactions. He then rang up an official in the Town & Country Planning department to verify the facts of the case. That gentleman confirmed that the information in the sale deed was correct.”

He was brief and to the point: Do not probe further or create a problem by sharing this information with others. It was clear to Khemka that the deal in question was not above board, because it involved sidestepping rules and a substantial loss to the Exchequer. On the other hand, as a loyal bureaucrat, he was expected to behave like Gandhi’s three monkeys and remain blind, deaf and mute.

But Khemka preferred not to lie like a prostrate, disemboweled Gulliver. He stepped up the heat, and walked that extra mile. Indian bureaucracy’s Forever-In-Transit man never gave up against the pressures, he just paid the price of being straight. The book shows how it is for the bureaucrat to remain firm on the decisions, and not play garden-garden as wonderfully depicted in Anurag Kashyap’s two part classic, The Gangs Of Wasseypur.

A brilliant read.