Book Review: The Royal India Navy Mutiny.

Pramod Kapoor breathes life into a partly forgotten event of 1946.

In an article dated February 21, 1946, New York Times reporter George E Jones said the following: “The mutiny of sailors of the Royal Indian Navy is regarded here as potentially the most disturbing in the series of riots and demonstrations among Indians, starting last November with outbreaks in Calcutta.”

“Since then, there have been other large scale civilian demonstrations, riots in Bombay and Calcutta—mostly centering on the trials of “Indian National Army” men—and hunger strikes among Royal Indian Air Force Personnel for better food and living conditions. The present clashes in Bombay and Karachi however, are the first time that Indian armed forces have actually mutinied in this violent fashion.”

The British empire, it is now on records, was petrified and politicians in London felt the 1946 uprising could assume the proportion of the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny. But good sense prevailed and Sardar Vallabbhai Patel —also called the Iron Man—pledged his equity and negotiated peace. Publisher and author Pramod Kapoor’s brilliantly researched tome, 1946: Royal Indian Navy Mutiny (Last War of Independence) highlights this crucial piece of information that – I have a feeling – got lost in the pages of history books in India.

So how serious was the case? Clement Attlee, Britain’s post-war Prime Minister who succeeded Winston Churchill, got into the act immediately. His telegrams to India, claims the New York Times, did not get any immediate answers about the uprising but Attlee was sure that the support of Indian military—army, air force and naval personnel—could no longer be taken for granted. The book helps the readers understand another crucial fact: That in World War-I and World War-II, Indian troops had been gun fodder for the imperial power but now—around 1945-46—things were changing. So the best option for Britain was to opt for discretion and leave India, long considered the “Crown Jewel” of the Empire.

The 1946 uprising was serious. India was on fire because the British rulers were conducting trials of soldiers of the Indian National Army (INA) inside the expansive Red Fort in the Indian Capital. And then, the Naval mutiny was too hot to handle. The two incidents triggered the sending of the Cabinet Mission and the subsequent decision to grant freedom. Interestingly, two decades after India gained freedom, John Freeman, the then British High Commissioner in New Delhi, told a gathering that the 1946 mutiny had petrified London that 1857 may be repeated.

The Indian government saluted the 1946 mutineers by mentioning them in the Indian Navy tableaux in this year’s parade. Political cognoscenti called it a rarest of rare gesture. Incidentally, never before have the armed forces saluted the memory of those who rose up in arms against the established order.

Let’s get back to the book of these unsung heroes. Poor service conditions, racial discrimination and anger at the court martial of rebel soldiers of the Indian Nation Army (INA) were the primary reasons for the mutiny.

The first spark happened on February 18, 1946. It was a Monday, and the time was 0800 hours. A group of 1600 sailors of the RIN battleship HMIS “Talwar”, docked at Colaba in Bombay, went on strike. They had been complaining about food, which was of low quality. Only poorest quality rice, garnished with stone chips and mud pieces, was supplied. The rating’s uniform was made of cheap and coarse material. The ratings were tired of this routine insult.

The sailors walked out of the mess hall because of inadequate food and started raising slogans: “No food, no work.” The next day another 20,000 ratings joined the strike, and over the next couple of days, rioting broke out. The Communist Party of India, which had a sizable following among the working class in Bombay, immediately extended support. Congress and Muslim League were critical. The mutineers did not discriminate, they were seen by many hoisting the tricolour of the Congress, green streamer of the Muslim League and the red flag of CPI on as many as 78 ships. The sailors urged residents of Bombay to rise in support of their revolt—the greatest in naval history—spreading to 22 units all along the Indian coastline, from Karachi to Calcutta. The strike spread like wildlife. Several processions were taken out in Bombay, Karachi, Calcutta and other places in the subsequent days. India’s harbours looked like war zones even as Indian ratings and British soldiers clashed. I read in another report how the ships’ sirens were blaring and strikers were using loudspeakers to call ordinary citizens and Indian troops to throw the British back into the sea.

Some 400 Indians died of bullet wounds and 1500 suffered injuries after soldiers of the British Military and police (in cities where demonstrations took place) fired indiscriminately on the demonstrators. In a quick move, the sailors formed the Indian National Navy, on lines of Subhas Chandra Bose’s INA and saluted the British officers with their left hand as a mark of their rebellion.

Encouraged and pushed by Patel, the sailors surrendered on February 24, 1946. So what did this mutiny achieve? Kapoor says it accelerated the transfer of power. Let’s not forget that this mutiny caused public disagreements between Mahatma Gandhi and Aruna Asaf Ali, who secretly advised the naval ratings during the mutiny. Serious rift emerged between Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel. Kapoor says the naval mutiny of 1946 was among the hardest blows the British received in their 200 year rule in India.

And there were other fears for the British. Britain realized that without the support of the navy, approximately 100,000 British troops, administrators and civilians and their families were in no position to make it to Britain safely. Many could have been slaughtered, the British quit India the following year. I remember some notes from Mutiny of the Innocents, written by BC Dutta, a telegraphist who joined the RIN in the Communication Branch in 1941. Writes Dutt: “We found ourselves working alongside white servicemen from the army. In the Indian Army, British servicemen received preferential treatment. Whether at base or in a combat zone, they had better accommodation, better amenities. They were paid five to ten times more for the same jobs that Indian servicemen did. They travelled more comfortably. They could, if they wished, use Indian servicemen’s canteens, mess rooms and baths, but the Indians had no access to theirs. The British servicemen were not required to salute the viceroy’s commissioned officers. The discrimination was crude and was calculated to make the Indians feel inferior to the British.”

Writes Kapoor: “Indian ratings got a taste of what life would be like in the Royal Indian Navy from the day they joined. As a rating wrote in a letter home: Officers do not act according to printed regulations but make their own rules. Now it was not just British officers. Even Indian officers treated them the same way. Kapoor says the indiscriminate use of abusive and foul language was seen as a symbol of authority. “Bastards, baboons or swines were common phrases heard in the Navy along with bloody, behen chod, blackies and black bastards.”

Beautifully, Kapoor scripts the story of the mutiny, explaining the central characters and who started the first planning. I learnt the first planning for the mutiny took place in a flat on Marine Drive, overlooking the Arabian Sea. And the two who planned it were Pran and Kusum Nair, the last named a journalist very active in the underground freedom movement.

Now, unlike the First War of Independence in 1857, when Indian mercenaries bailed out the British by mercilessly mowing down the revolutionaries, this time Indian soldiers were not favourably disposed towards their colonial masters. For instance in Karachi, Gurkha troops refused to fire on the sailors.

The book explains how the violence started. On February 21 the British deployed their shock troops who opened fire on the sailors as they came out of their barracks in Bombay. This turned a peaceful uprising into an armed rebellion. Indian ratings and British troops fought pitched battles throughout the day in Bombay and Karachi.

The atmosphere was further poisoned by Admiral Godfrey’s order to completely destroy the Indian Navy. The British surrounded the rebel fleets with few loyal vessels. A reinforcement of battleships from Trincomalee in Sri Lanka reached the Gateway of India in Bombay. British bombers and fighter aircraft of the RIAF carried out threatening sorties over the rebellious fleet. In Karachi, the British sent in the murderous Black Watch, an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

There were other issues. Former PM Morarji Desai, who took over as Home Minister of Bombay a few months after the mutiny, displayed a total cavalier attitude towards freedom fighters. He said the sailors had no right to rebel. Desai even said INA was not the harbinger of independence and it was Gandhi who brought independence for the country.

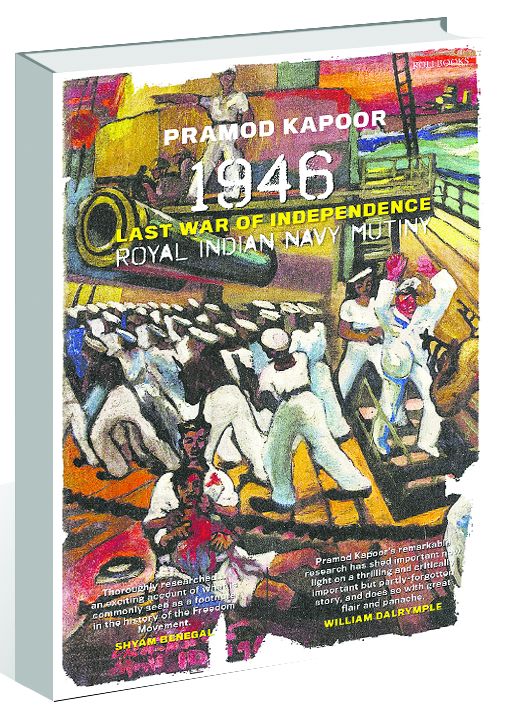

I am told the book’s cover illustration is a painting by a Chittagong-born artist, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, who was witness to the events in Bombay in 1946 and was present in Kamgar Maidan when residents of Bombay, especially the working class, rallied in support of the mutiny on 22 February 1946.

Unquestionably, Kapoor’s work is the most lively account of the last war of independence. Probably now the naval mutiny will no longer be consigned to a footnote in most histories. Now, it will surely find its place of pride in the history of the freedom struggle.

Time for Kapoor to pen a fascinating tome on the 1971 liberation war that gave birth to Bangladesh. I am sure he will do justice to another slice of history that remains buried in libraries because of lack of research.