Conflict is not a new phenomenon to democratic societies. This is more so in India, with its large and diverse heterogeneous population comprising several distinct geographies, languages, religions and ethnicities, which increase vulnerability levels manifold. Economic and social disparities and governance deficits within the country further exacerbate such vulnerabilities. Consequently, India has faced multiple insurgencies in various parts of the country since independence. These include insurgencies in the Northeastern states, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab as also in a vast swathe of territory, on the Eastern side of the country, stretching from West Bengal down to Telangana, which has been afflicted with Left Wing Extremism (LWE).

India’s record in dealing with internal armed conflict (insurgencies and terrorism, sometimes also referred to as low intensity conflict), has been a mixed one. It has never allowed the situation to escalate to a level of civil war, and it has never lost a counter insurgency campaign.[1] However, the nation has successfully resolved conflict in only three of its counter insurgency campaigns—Mizoram, Tripura and Punjab. In all other cases, the insurgencies though contained, continue to persist, such as in Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, J&K and in LWE affected districts, popularly called the Red Corridor. This indicates that while India has been successful at ‘conflict management,’ its record in ‘conflict resolution’ has not been of the same order, which in turn condemns its security forces to containing insurgencies and terrorism indefinitely, at great human and financial cost.[2] This paper looks into causative factors leading to LWE and the states response. It will also analyse policy options for conflict resolution.

Left Wing Extremism

Left Wing Extremism is a term used for violence inspired by a virulent communist ideology, which seeks to overthrow the existing order through the barrel of a gun. In India, the proponents of such violence are referred to as Maoists or Naxalites. The Communist Party of India (CPI), which came into existence on 17 October 1920 in Tashkent,[3] had by the time of India’s independence, achieved salience in West Bengal and the Telangana region of the erstwhile Hyderabad state. The actions of the CPI were centred around mass mobilisation to achieve land reforms. In Telangana, the movement became an armed struggle which the Indian Army quelled by October 1951. In West Bengal, an essentially agrarian movement became an armed struggle, following the death of nine adults and two children in police firing in a small hamlet called Bengai Jote near Naxalbari village in the Naxalbari Block in Siliguri district on 25 May 1967.[4] This gave rise to the terms Naxalism. The uprising was crushed in 72 days, paradoxically, by a communist backed Left Front government, which had by then gained power in the state.[5] The Chief Minister triumphantly declared the end of the Naxal Movement but that was a premature assessment as the nascent Naxalite movement which was spawned was destined to grow. It was crushed again in 1971, this time by using the Indian Army (Operation Steeplechase: July August 1971),[6] but like a phoenix, it rose again from the ashes. The severe body blows received by the movement both in Telangana and West Bengal, made its leaders realise the need for establishing a base in remote jungle areas that would suit guerrilla operations and which could be used by them for resuscitating the movement. Accordingly, in the eighties, the Peoples War (PW) and Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCCI) shifted their base to the densely forested and hilly tracts of Andhra Pradesh and Orissa.[7] Later, they shifted to the jungle areas of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. In September 2004, the MCCI merged with PW to form the CPI (Maoist). The press statement released to mark the merger stated… ‘Armed struggle will remain as the highest and main form of struggle and the army as the main form of organisation of this revolution.’ The statement also declared that… ‘The two guerrilla armies of the CPI(ML)[PW] and MCCI—the PGA and the PLGA— had been merged into the unified PLGA (Peoples’ Liberation Guerrilla Army) and that hereafter… ‘the most urgent task of the party was to develop the unified PLGA into a full- fledged People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and transform the existing Guerrilla Zones into Base Areas, thereby advancing wave upon wave towards completing the New Democratic Revolution’.[8]

The Party Constitution gave as its immediate aim, the overthrow of the government through Protracted People’s War and to establish a dictatorship under the leadership of the proletariat.[9] With the merger, the long process of centralisation of semi-anarchist groups around two centres—the MCCI and PW—was thus brought to culmination.[10] The trajectory of the movement thereafter took an upward spiral, and by 2010 had affected 196 districts of India forcing the then Prime Minister to declare in May of that year that Naxalism remained India’s biggest internal security challenge and control of Left-wing extremism was imperative for the country’s growth.[11]

Naxal violence has shown a consistency which till date has belied hopes of an early end to conflict. Since 2004, violence levels escalated all across the affected areas, peaking in 2010 when LWE claimed 1180 lives, of which 626 were civilians and 277 were security forces personnel. During this period, 277 terrorists from various outfits, mostly from the CPI (Maoist) were eliminated.[12] In 2011, violence levels came down to half of the 2010 figures and these were halved once again in 2012, but since then, there has been a remarkable resilience and tenacity on the part of various Maoist outfits to continue to inflict casualties on the security forces and to unarmed civilians, albeit on a smaller scale than in the period 2004-2012.

The geographical spread of areas affected by Maoist violence has however shrunk, with some of the earlier affected states like West Bengal, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh reporting zero incidents of violence in their affected districts. There has also been a dramatic decline in violence levels in the affected districts of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar and Maharashtra, which together had but four SF fatalities and 28 civilian fatalities related to Maoist violence in 2018 (Jan-Sep). During this period, in the above districts, terrorist casualties were reported as 62.[13] Replying to a question in the Rajya Sabha on 14 March 2018, Shri Hansraj Gangaram Ahir, Minister of State in the Ministry of Home Affairs stated that 106 districts in 10 States are included in the Security Related Expenditure Scheme of the Government for Left Wing Extremism (LWE) affected States. He added that in 2017, only 58 districts in the country reported LWE violence.[14] As per a senior Home Ministry official quoted by the Times of India, post a review carried out in the Ministry, the number of Naxal affected districts have been brought down to 90, of which 30 are the most affected. Of the 30 most affected districts, 13 are in Jharkhand, 8 in Chhattisgarh, 4 in Bihar, 2 in Odisha and 1 each in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra.[15]

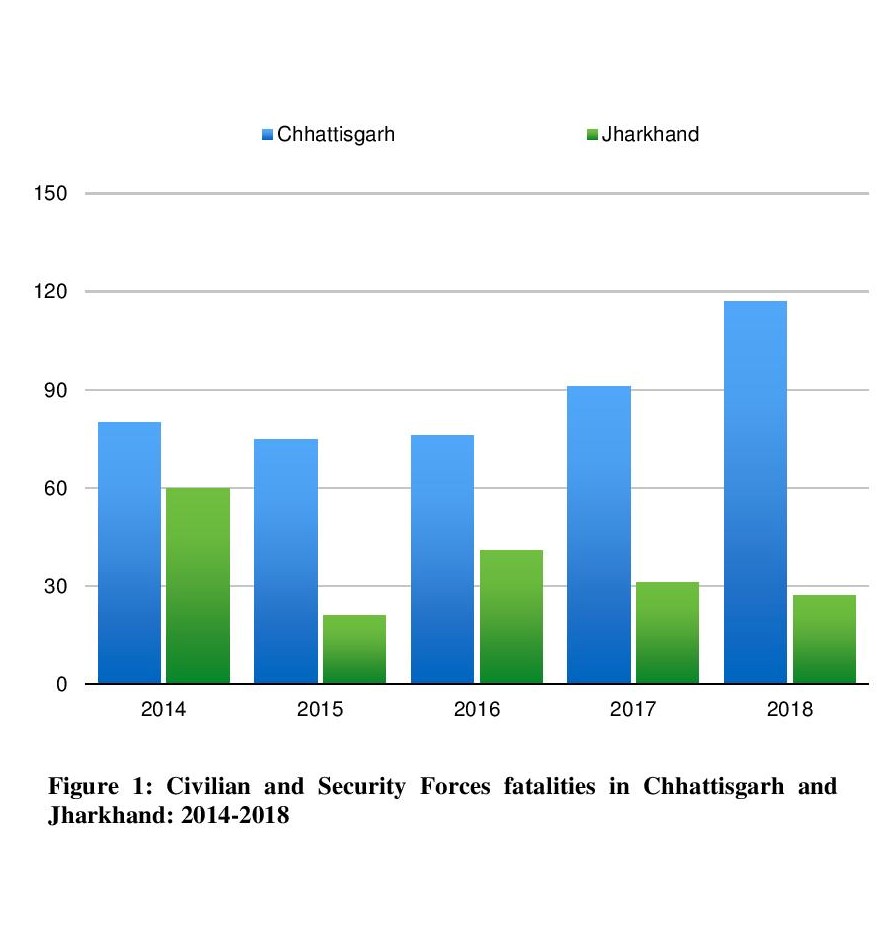

Development and security related measures undertaken by the concerned states has caused an improvement in the security environment and has led to a shrinkage of the areas under Maoist influence. Political penetration in areas which earlier were under Maoist control has also played a role in shrinking Maoist influence. However, in the two critical states of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, violence levels have not shown a declining trend (See Figure 1). This is the base area of the Naxals, which affords protection to the insurgents due to dense jungles, underdevelopment and paucity of roads and tracks, which makes movement difficult. In 2018 (Jan-Sep), these two states accounted for 60 civilian fatalities and 54 SF fatalities, which in terms of SF fatalities was about 14 times and in terms of civilian fatalities, over half the number suffered in all other states combined. This is worrisome and gives rise to the possibility of a further expansion of Maoist activity into the neighbouring region, if left unchecked.

Some of the major attacks that have been carried out by the Maoists against the security forces in 2018 are as under:

• 24 January: 4 SF personnel killed in Narayanpur district, Chhattisgarh.

• 13 March: 9 SF personnel of the Chhattisgarh Cobra Force killed in a land mine blast in Sukma district, Chhattisgarh.

• 20 May: 7 SF personnel killed in Dantewada district, Chhattisgarh.

• 26 June: 6 Jharkhand Jaguar Force personnel killed in land mine blast in the Chinjo area of Garhwa district.

• 11 July: CRPF constable killed in an attack in East Singhbhum district of Jharkhand.

• 27 October: 5 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel killed and one injured after Maoists blew up their bulletproof bunker vehicle in Bijapur district, Chhattisgarh.

• 30 October: Doordarshan staffer and two SF personnel killed in a Maoist attack in Dantewada district, Chhattisgarh.

• 8 November: A soldier of the Central Industrial Security Force (CISF) and four civilians were killed when an improvised explosive device tore through a private bus in Dantewada district.

• 11 November: Maoists trigger 6 IED blasts in Kanker and attack a BSF patrol in Bijapur, killing a BSF sub inspector.

The above attacks make it clear that the Maoists retain the ability to strike in their chosen areas against the police forces operating against them. The 27 October attack by the Maoists in Chhattisgarh which were followed by a few more attacks in November were an attempt to enforce a boycott of the polls. Despite threats of violence, the people came out and voted in large numbers in both phases of the polls on 12 and 20 November, which augurs well for the state and indicates that the support which the Maoists expected from the masses is not forthcoming. Earlier, on 7 October, Home Minister Rajnath Singh, while addressing troops of the Rapid Action Force on their 26th anniversary in Lucknow, stated that the number of districts affected by Naxal violence has reduced to 10-12 districts from the earlier 126 affected districts and expressed optimism that Naxalism will be wiped out within three years. While one can laud the optimism of the Home Minister, the ground situation as of now does not point to an early end to conflict. It may take a decade or more to restore normalcy, depending on whether the respective states and the Centre muster the requisite will to deal with the Naxalite leadership, especially their urban support base with a firm hand and at the same time, improve governance and justice delivery mechanisms, to restore confidence within the public to wean them away from the clutches of the terrorists.

State Response: Right Policies, Poor Implementation Mechanisms

The Centre’s efforts to deal with LWE is premised on a holistic approach, wherein security and development go hand in hand with ensuring rights and entitlements of local communities, improvement in governance and public perception management. Poverty alleviation programs are an important part of the focus of the state governments which are being assisted by the Centre. Legislation has also been enacted to protect tribal rights and interests. The approach is pragmatic and logically should have led to conflict resolution, especially as LWE, unlike the other festering insurgencies and terrorism within the country, is an indigenous movement which is not externally inspired, and even today has but limited support from external actors. If the policies are right, then obviously we need to look into why the Naxal movement continues to thrive.

One of the causative factors is the federal structure of the country, whereby law and order is a state subject and is not on the concurrent list of India’s Constitution. Interventions by the Centre in Maoist affected states can only be forthcoming if the affected state requests for assistance. The Centre’s role thereafter is restricted to monitoring the situation in the affected states and coordinating their efforts. The Centre also provides Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF) to supplement the security efforts of the States, assists in training through setting up Counter Insurgency and Anti Terrorism (CIAT) schools; modernisation and upgradation of the state police and their intelligence apparatus; reimbursement of security related expenditure under the Security Related Expenditure (SRE) Scheme etc. The underlying philosophy is to enhance the capacity of the state governments to tackle the Maoist threat in a concerted manner.[16] However, once the Centre intervenes and provides assistance, the state governments dither on taking ownership of the problem and remain lackadaisical in building indigenous capacities.

Another area of concern is that government departments, whether in the Centre or in the state, seldom ‘think, speak and act in concert’. There is also marked lack of unity in effort in all the agencies involved in countering the insurgent threat. There also is an apparent lack of political consensus between the elected representatives of the state and of those in the Centre, which inhibits political solutions from coming to fruition. State governments usually follow a political approach, which is soft and inconsistent and the Centre has not been able to force a change of attitude which would result in a more robust policy to deal with the insurgents. The Central government, apparently, has also not been able to impress upon the states to implement vital administrative reforms or achieve the desired levels of cooperation and coordination between the Centre and the states and between the affected states. The common denominator here can be summarised as a failure to build adequate indigenous counter insurgency capacities by the affected states, lack of unity of effort within government agencies and lack of political consensus.[17] A possible solution could be an amendment to the Constitution, whereby law and order could be placed on the concurrent list. This however will meet with tremendous resistance from the states, which would view it as an imposition by the Centre and an attempt to usurp the powers of the state governments. Economic packages are at times thought to be the panacea for resolving insurgencies.

There is certainly an element of economic deprivation which drives insurgencies, and development of the area must certainly be a key intervention to conflict resolution. The Centre has not been tardy in allocating resources to the affected states for boosting economic development, but the mere infusion of aid achieves little. Most states are unable to absorb the massive infusion of aid, but more importantly, poor financial oversight and lack of accountability result in its improper utilisation. In many cases, state funds have led to massive corruption, with part of the money also finding its way into the hands of the insurgents. [18]The state administration needs to focus on the utilisation of such aid and its impact on the security situation. The Centre on its part must make further grants contingent on results being visible on the ground.

A feature of LWE is the governments comfort level with the status quo, when insurgency is brought down to manageable levels. The urgency to seek a political resolution of the problem gets relegated as the government hopes that time and fatigue will erode popular support and that the insurgency will die a natural death. That this does not happen has been consistently seen in the ability of the Maoists to resurrect the movement, after they have received a severe mauling. The need of the hour is hence a national political consensus on issues that threaten the security of the country from within. Such an approach has eluded every government thus far. In the absence of a political consensus, it is difficult for the state government to offer a plausible political alternative. Another inhibiting factor is the fact that political parties also seek the assistance of the Maoists, when it comes to fighting elections. In the recent elections to the Chattisgarh Assembly, Mr Raj Babbar of the Congress called the Naxals ‘revolutionaries,[19] a comment which was severely criticised by the Prime Minister and others. Earlier, in 2010, Mr Digvijay Singh had stated in response to a question in a TV interview on the Maoists that, “No one can defend their criminal activities. But they are not terrorists”.[20] Policies thus get constrained when harder options need to be applied for conflict resolution, which once again reaffirms the need for a national political consensus on national security issues.

A cardinal principal of anti insurgency operations is to separate the insurgents from their support base. The base of the movement is now in the tribal community mostly found in the Gond forests of Central India. With a population of over 13 million people, spread over 12 states,[21] the Gonds are one of the largest tribal group in the world and are widely spread in Bastar district of Chhattisgarh, the Chhindwara District of Madhya Pradesh, and also in the parts of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Odisha. The conflict between the Maoists and the government often finds the tribal and other affected population groups caught in between, which further fuels violence. In many areas, the Maoist writ runs alongside that of the state. In some of these areas, where the state administration is totally absent, it is Maoist ‘laws’ that are in effect and not the Indian Constitution.[22] Efforts by the state administration to wean away the tribals from the clutches of the Maoists have had little impact, primarily because of an inability to converse with the local population. About 95 per cent of the Gondi population have no knowledge of any language other than their own, so they get left out in any discourse which seeks to ameliorate their living conditions. There is a dire necessity of the state functionaries to deal directly with this mass of people rather than with the smaller five per cent who they seek to engage and who being better off economically and more closely aligned with the non tribal populace, have little to offer in terms of projecting the interests of this vast majority. It is imperative that the security forces and the local administration develop the skills to communicate with them. This could be through learning the Gondi language and also through developing translation tools. The tribals also need to be assisted in projecting their requirements through mobile phone based apps, which could enable two way interaction and help in creating better levels of understanding between them and the state. This will go a long way in weaning away the tribals from the clutches of the Maoists.[23]

Another area requiring attention is intelligence, training and leadership. Newspaper reports of the attacks that have taken place against the police forces invariably state that the Naxals were in large numbers, sometimes in the range of 300 to 400 fighters. This may well be a gross exaggeration, but even if the attacks were carried out by smaller numbers of 30 to 40 Maoists, it is difficult to comprehend why the police forces were unaware of their presence. The attack on a large CRPF party in April 2010 in Dantewada is a case in point. Here, a force of 300 or so Maoists attacked the CRPF company in the Mukrana forest, killing 76 personnel, 74 of whom were from the CRPF and two from the local police.[24] That the police forces operating in the jungles were unaware of the presence of such large groups of insurgents in their immediate vicinity, points to serious shortcoming in operating methodology, especially in terms of patrolling, field craft, battle drills, and most importantly, their ability to operate by night. The area they can dominate thus gets restricted to the immediate vicinity of their post and makes them easy targets for the Maoists as and when they venture out. Another vital pertains to leadership, which remains a weakness in the CAPF. Only through good leadership and effective training can area domination be achieved, which will put the Maoists on the back foot. This is not a facet which can be addressed through technology, such as the use of drones. Technology is a useful force multiplier, but in the absence of well trained and well led police forces, technology can have little impact on ground operations.

The bulk of weapons held by the Maoists are locally manufactured crude weapons, mostly muzzle loaders, 12 gauge shotguns and 9 mm Sten guns. Weapons seized by the police forces in various anti Naxal operations have largely been of such types. The more sophisticated weapons such as the AK series of rifles and the INSAS and SLRs are held by the Maoists in lesser numbers. These have either been snatched from the police forces or have been purchased. The Naxals do not appear to be overtly short of weapons, ammunition or explosives which indicates that the state has not been particularly successful in neutralising the sources of supply of weapons to the Naxals, and points to an area which needs greater focus and application. There also does not appear to be any appreciable impact of the efforts by the state to curb terror financing. Demonetisation did have a temporary effect, but the Maoists seem to have recovered from that shock. Maoist financial collections are assessed to be of the order of Rs 140 crore per annum, the sources being business establishments, industry, contractors, corrupt government officials and political leaders. The major part of Maoist revenue comes from the mining industry, PWD works, and collection of tendu leaves. Taxes are also levied by the Maoists in their strongholds and there is a symbiotic relationship between Maoists and illegal mining as well as forest produce. A large part of this amount comes from extortion, where paradoxically, all the actors get a share in the pie —the contractors, the Maoists and the public servants. Greater focus of the government in squeezing Maoist finances is necessary if the Maoist threat is to be neutralised. This must hence be a prime intervention of both the state and Central governments.

Article 244 of the Indian Constitution and the Fifth Schedule, provides statutory safeguards to the tribal population.[25] PESA [Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas)] Act, 1996 goes further to protect tribal rights by providing for tribal self-governance and recognising the traditional rights of tribal communities over their natural resources. Schemes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), 2005, and the more tribal-specific Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, better known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA) are seen to be beneficial in preserving the rights of the tribal people. The government has also formulated the National Rehabilitation & Resettlement Policy, 2007, with a view to striking “a balance between the need for land for developmental activities and, at the same time, protecting the interests of the land owners, and others…whose livelihood depends on the land involved.” It also makes mandatory social impact assessments and provision of infrastructure and amenities in the resettlement areas.[26] However, while the government has used a range of political, legislative, developmental and military measures to pursue their goals, the political and constitutional means have not been pursued with the intensity that was required. Rather, more often than not, both the Constitutional provisions and the enacted legislations have been violated. Tribal land has been acquired for development and mining activity in gross violation of formulated laws. And the Governors of the states have singularly been tardy in implementing the provisions of Article 244 of the Constitution.

Left Wing Extremism draws sustenance through espousal of their ideology, which runs counter to the idea of Indian democracy. The conflict in India’s heartland is thus a battle between democracy and all that it stands for versus a dictatorship involving the suppression of the very freedoms democracy believes in. For democracy to win this battle, it must be perceived to be a functional and worthwhile entity. This would require a visible and effective justice delivery mechanism to the poorest in India’s heartland, transparency in governance, empathy on the part of government officials and targeted socio economic development. However, many of the lower level functionaries of the state, who interact with the locals—like the forest guard and the local constable, to name but a few—are themselves perceived by the tribals and other deprived sections of society to be agents of suppression and exploitation. There is thus a need for greater empathy from all government agencies. Good governance and an effective justice delivery mechanism are also key issues that need to be addressed.

The Naxal challenge primarily remains that of development, governance and rights delivery. Today, we need to provide good governance in the worst of law and order environments. To that purpose, a better civil administration structure would need to be created in place of the model we presently have. This could draw upon the best officers from across the country, as a replacement of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) in the LWE affected areas. This could be constituted on the lines of the former Indian Frontier Administrative Service (IFAS), which unfortunately was merged into the IAS.[27]

Conclusion

The attention of the government is focussed on a holistic approach to combat Left Wing Extremism, but the Indian State still suffers from feudal mindsets, mis-governance and corruption. Solutions lie in proper implementation of the various initiatives taken by the government to address the concern of the tribal population and the marginalised sections of the population living in India’s heartland. In the absence of improvement in governance mechanisms, the cycles of violence and counter violence will continue indefinitely, which will retard India’s progress in becoming a strong regional and global player. It is difficult to fault the approach of both the Centre and the States. What needs to be addressed are the mechanisms to implement the governments intent.

In terms of a

whole of government approach, the government must function within the ambit of

law and ensure that Constitutional safeguards to the tribal population are

protected and enforced, in letter and spirit. In terms of governance

capacities, the institutions of the state must be resurrected and made

effective, to include justice delivery mechanisms and an effective civil

administration. The whole of government approach must involve all instruments

of state power—political, diplomatic, economic,

social, administrative and military in a holistic manner and ensure unity of

effort. And finally, the government must mobilise the population through an

effective perception management campaign. For the police forces operating in

the area, a cardinal principle must be to win the faith and trust of the local

population through empathy and focussed intelligence based operations. This is not an easy ask—but this is

the only way to ensure that this long running insurgency in India’s heartland

becomes a thing of the past.

[1] Ganguli, Sumit and Fidler, David P (Eds), India and counter insurgency: Lessons learnt (New York: Routledge, 2009) pp 5, 225.

[2] Nanavatty, Rustom K. Internal Armed Conflicts in India, 2013, New Delhi, Pentagon, pp 1-3.

[3] https://cpim.org/history/formation-communist-party-india-tashkent-1920

[4] Shamanth Rao, The Remains of Naxalbari, available at https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/ qILQtLkiUnpvkRP9v3aV3O/The-remains-of-Naxalbari.html, accessed on 1 October 2018. The pic of the memorial at Bengai Jote is available at http://cpiml.org/feature/resolution-on-naxalbari/ attachment/img_20170525_105151/

[5]In the 1967 elections held for the state assembly in West Bengal, two broad based fronts were formed against the ruling Congress Party. These were The United Left Front (ULF) and the Progressive United Left Front (PULF). The CPI (M) was the major constituent of the former and the Bangla Congress of the latter. The Congress was defeated and both these fronts joined hands to form the United Front government in the state.

[6] http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/left-wing-extremism/

[7] http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/left-wing-extremism/

[8] Press statement, People’s March, available at http://www.bannedthought.net/India/PeoplesMarch/PM1999-2006/ archives/2004/nov-dec2k4/Merged.htm , accessed on 22 November 2018.

[9] http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/maoist/documents/papers/partyconstitution.htm, accessed on 17 November 2018.

[10] For a chronological summary of the various phases of the many Communist insurrections since 1948, see the Hindustan Times of 3 January 2007.

[11] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/Naxalism-biggest-threat-to-internal-security-Manmohan/ article16302952.ece

[12] http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/maoist/data_sheets/fatalitiesnaxal05-11.htm

[13] Ibid.

[14] https://mha.gov.in/MHA1/Par2017/pdfs/par2018-pdfs/ls-14032018/2121.pdf

[15] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/centre-removes-44-districts-from-list-of-maoist-hit- areas/articleshow/63787192.cms

[16] https://mha.gov.in/division_of_mha/left-wing-extremism-division

[17] Nanavatty, pp 48,49

[18] Ibid

[19] https://www.jagran.com/elections/chhattisgarh-congress-leader-raj-babbar-sees-revolutionaries- in-maoists-18603457.html

[20] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Maoists-are-not-terrorists-Digvijay-Singh/articleshow/ 5924039.cms

[21] Census of India 2011: A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix

[22] CLAWS team field trip to Chhattisgarh in Oct 2010.

[23] Talk delivered by Shubhranshu Chowdhary on Future course of Naxal movement and its impact, in a National seminar on Changing contours of internal security in India: Trends and responses, hosted by the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) on 3 November 2018

[24] The Hindu, 6 April 2010

[25] Article 244 relates to the Administration of Scheduled Areas and tribal Areas. It states that the provisions of the Fifth Schedule shall apply to the administration and control of the Scheduled Areas and Scheduled Tribes in any state other than the state of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram which are covered under the Sixth Schedule. Part A of the Fifth Schedule states that the Governor of the state having scheduled Areas shall annually, or whenever so required by the President, make a report to the President regarding the administration of the Scheduled Areas in the state and the executive powers of the Union shall extend to the giving of directions by the State as to the administration of the said areas. Part B of the Schedule mandates the establishment of Tribes Advisory Council consisting of not more than twenty members, of whom three fourth shall be the representatives of the Scheduled Tribes in the Legislative Assembly of the State. These seats are to be filled in by the other members of the tribe if adequate number of representatives is not available in the Assembly. The Governor has the power to notify that any particular act of the state shall not apply to the Scheduled Areas. The Governor may make regulation for these areas and may repeal or amend any act of Parliament or of the Legislature of the State. No regulation shall be made without consultation with the Advisory Council.

[26] For text of the policy see, Government of India, Ministry of Rural Development, (Department of Land Resources) (Land Reforms Division) Resolution dated 31 October 2007, available at http:// dolr.gov.in/sites/default/files/National%20Rehabilitation%20%26%20Resettlement%20Policy%2C %202007.pdf, accessed on 21 November 2018.

[27] A special service known as the Indian Frontier Administrative Service was established in 1957, to administer the Northeastern states. This service was doing a commendable job of adequately administering the Northeastern states with due regard to cultural and tribal sensitivities of the people. For reasons best known to the government, the Indian Frontier Administrative Service was abolished in the latter half of the sixties and merged into the IAS.

how can you help us in bangladesh?